A Realization of Tomorrow: An RCC Fellow Reflects on the NYC March to End Fossil Fuels

On September 17, I joined an estimated 75,000 activists in a climate march through the streets of New York City to end fossil fuels.

The morning of the March, I went to the gym at 7am for an arm workout, not realizing that my arms—not my legs—would soon be screaming in protest from four hours of waving a sign at the front of the Youth Hub.

I donned my Rachel Carson Council t-shirt, a pair of walking shoes, and an edgy nose ring—not realizing I would end up on the front page of the New York Times.

And I stuffed three granola bars into my bag—not realizing that I would scarf all of them down in one sitting at a 5 PM rally standing 3 feet away from Bill McKibben.

There was a lot that surprised me about the March, even as a frequent attendee of climate protests.

The most delightfully unexpected aspect of the March was that it felt like a festival.

Is that allowed? I asked myself. To simultaneously celebrate our wins and air our grievances? Ultimately, the March reminded me that a joyful protest does not lose its urgency in any way.

There have been a considerable number of climate wins over the past two years, from the passage of the $369 billion Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 to New York University’s divestment from fossil fuels only days before the March.

There have been a considerable number of climate wins over the past two years, from the passage of the $369 billion Inflation Reduction Act in 2022 to New York University’s divestment from fossil fuels only days before the March.

These victories likely fed into the colorful, raucous ambience of the March, with joyful reunions between cross-college student groups, hilariously stinging chants about famous oil and gas companies, and selfies at every street corner. Somewhere in the streets, activists danced atop a decorated school bus. Music echoed through the city. It was truly a “divestival.”

But the March was not without its demands. Lives are at stake. In one of the most vibrant and intergenerational protests I have ever witnessed, I joined the crowd in chanting our conglomeration of “asks”:

- To President Biden, halt all new fossil fuel projects and declare a climate emergency.

- To the United Nations—meeting just down the road for General Assembly and Climate Week—use your powers to implement a systemic just energy transition with provisions for water, soil, ecological health, and equity.

- To the dwindling leftovers of the climate denial movement…get over yourselves.

There was something nostalgic about the protest. As clichéd as it may sound to say that the March echoed the 1970s, my surroundings felt like how I would’ve imagined the decade. Art, music, creativity, and rage abounded.

There was something nostalgic about the protest. As clichéd as it may sound to say that the March echoed the 1970s, my surroundings felt like how I would’ve imagined the decade. Art, music, creativity, and rage abounded.

I conversed with an ocean activist twirling a “jellyfish” parasol dangling with tendrils of yarn. I watched a man parade the streets dressed fully as a snowman, complete with a suit of cotton balls. Some activists carried an inflatable pipeline that spanned dozens of rows of protestors.

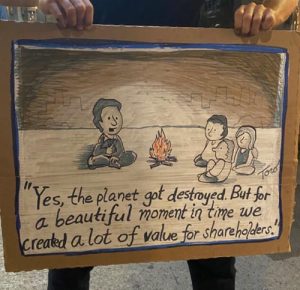

The sign I carried depicted a famous New Yorker cartoon by Tom Toro. “Yes, the planet got destroyed. But for a beautiful moment in time we created a lot of value for shareholders.”

An elderly woman approached me on the subway and asked about my sign. I bristled, ready to defend myself against the anti-climate comment she was surely about to make. Instead, she smiled, told me she was marching too, and asked for directions to 56th and Broadway.

An elderly woman approached me on the subway and asked about my sign. I bristled, ready to defend myself against the anti-climate comment she was surely about to make. Instead, she smiled, told me she was marching too, and asked for directions to 56th and Broadway.

One of my friends, Shubhangi, volunteered to be a marshal at the event. She later told me, “My job was boring, in many ways. I didn’t have to push or hold anyone back. Everybody was peaceful.”

Yet it was the first time I have blocked traffic. As I walked through the intersection, I tried to make eye contact with several of the drivers to gauge their facial expressions, offer a nod of acknowledgement, or pinpoint the location of intermittent angry honks.

There were several angry honks. However, it stood out to me that most stranded drivers did not honk but sat in stunned silence. Maybe it was out of reverence for youth turnout. Maybe it was resigned gratitude for the mildness of the protest compared to the recent activists who blocked Washington D.C. rush hour traffic by sitting in the road, or activists who threw soup onto famous paintings (both of which I consider equally controversial and unproductive).

Does protest work? I’ve talked at length about this in my book, Growing Up in the Grassroots, as well as in several of my other articles for the Rachel Carson Council.

The question has become so irritating to me that I refuse to answer it.

It’s not about whether protest “works.” It has never been a question of how many tons of carbon dioxide a protest draws out of the atmosphere or how many oil executives burst into tears afterward and pledge to change their ways forever. The reasons why protests matter—from antiwar, to AIDS justice, to civil rights and SNCC—are implicitly written into United States history.

The whole point of a demonstration like the March to End Fossil Fuels is that there is something unquantifiable about it. There is no way to quantify the lifelong impact of sending a “climate bus” of 56 Duke students up to the March to meet their climate heroes, or for activists to finally convene with their online collaborators face-to-face. (Towards the end of the rally, I bumped into Bill McKibben, who sent his love to the Rachel Carson Council.)

The whole point of a demonstration like the March to End Fossil Fuels is that there is something unquantifiable about it. There is no way to quantify the lifelong impact of sending a “climate bus” of 56 Duke students up to the March to meet their climate heroes, or for activists to finally convene with their online collaborators face-to-face. (Towards the end of the rally, I bumped into Bill McKibben, who sent his love to the Rachel Carson Council.)

The buzz of urgency and visibility surrounding a protest is one that permeates society in subtler ways than we realize. Did people show up for an issue? We did. And are elected officials responsible? Yes, we remind them of their duty. Hearing Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez speak about Biden’s accountability was a refreshing reminder that the climate movement is one patriotic enough to push pro-climate candidates to do even more.

All of that being said, there were tangible outcomes from the March.

All of that being said, there were tangible outcomes from the March.

Only three days later, Biden announced the creation of the American Climate Corps to employ young Americans in high-paying, unionized environmental jobs. It wasn’t a declaration of a climate emergency, but to me it is a resounding victory for young people and for climate jobseekers across the working class—foreshadowing the “march” forward into a revived New Deal ethic of hands-on stewardship, patriotism, and hard work.

If there had been no March, there would’ve been less impetus for NYU to strategically divest days beforehand—and perhaps for Biden to tactfully declare the American Climate Corps just three days afterwards. If protests serve as a calendar cutoff for making sweeping environmental announcements, all the better.

I spent my final night in the city strategizing with a group of youth ocean activists on the language of a speech to be delivered in front of U.N. officials later in the week. We strategized over slices of 99-cent New York pizza.

I spent my final night in the city strategizing with a group of youth ocean activists on the language of a speech to be delivered in front of U.N. officials later in the week. We strategized over slices of 99-cent New York pizza.

That rainy evening seemed to epitomize everything I’d cherished about the March: the pressured excitement of youth climate action merged with the fulfilling, casual opportunities to just enjoy each other’s company.

In an unintentional nod to the new Civilian Climate Corps and its callbacks to the New Deal, I had coincidentally written a quote from Franklin Delano Roosevelt on the back of my protest sign. It read: “The only limit to our realization of tomorrow will be our doubts of today.”

In an unintentional nod to the new Civilian Climate Corps and its callbacks to the New Deal, I had coincidentally written a quote from Franklin Delano Roosevelt on the back of my protest sign. It read: “The only limit to our realization of tomorrow will be our doubts of today.”

The March to End Fossil Fuels alleviated any doubts that we are in a climate renaissance.

Now, on the cusp of U.N. General Assembly meetings, COP28 in Dubai, and the final year of Biden’s first term, youth and world leaders alike must ask ourselves:

What will our realization of tomorrow look like?

RCC Presidential Fellow – Joy Reeves – Duke University

RCC Presidential Fellow – Joy Reeves – Duke University

RCC Presidential Fellow Joy Reeves is completing a Master’s degree in Environmental Management at Duke University’s Nicholas School of the Environment. Passionate about climate advocacy and scientific communication, she is the author of Growing Up in the Grassroots: Finding Unity in Climate Activism Across Generations (2020). Joy was previously an RCC Stanback Fellow and has held positions at the League of Conservation Voters, the Student Conservation Association, and the Wright Lab at Duke University, where she conducted research on the effects of saltwater intrusion and sea level rise on the coast of North Carolina. During her undergraduate career at Duke, she received her degree in Environmental Science & Policy with a minor in Visual Media Studies, as well as a Udall scholarship for environmental leadership and public service.