Bird of the Week

This flycatcher spends almost no time on the ground mainly because it cannot walk or even hop! It spends almost all its time high in the treetops chasing insects by swooping out for prey from a hunting perch with an unobstructed view and unobstructed flight paths.

This flycatcher spends almost no time on the ground mainly because it cannot walk or even hop! It spends almost all its time high in the treetops chasing insects by swooping out for prey from a hunting perch with an unobstructed view and unobstructed flight paths.

It hunts high up in the tree canopy which helps cut down on direct competition. Great Crested Flycatchers prefer hunting using multiple dead branches that have foliage around them for cover.

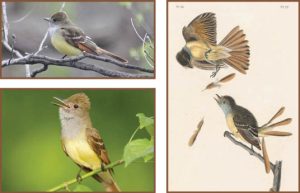

Unlike most flycatchers it is brightly colored with a lemon yellow belly and has a “great” crest.

Often hard to see high in the tree tops it can be easily identified by his loud “weeeeep” call.

Usually seen in forests, woodlands, and wooded parks, this edge-dwelling species prefers places where wooded areas adjoin grassy places, anything that creates openings in the woods increases habitat for them, unlike the threat this poses for other bird species.

Great Crested Flycatchers are secondary cavity breeders, meaning that they must build nests in tree cavities but cannot build these cavities themselves.

![]() Sign Up Here to Receive the Monthly RCC Bird Watch and Wonder and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts.

Sign Up Here to Receive the Monthly RCC Bird Watch and Wonder and Other RCC Newsletters, Information and Alerts.

Past Issues of the RCC Bird Watch and Wonder

When available Great Crested Flycatchers weave shed snakeskin into their nest. Although they prefer insects these birds also eat a fair amount of fruit which they swallow whole and regurgitate the pits. Males select a singing perch far from branch ends to conceal themselves. Nestlings rarely return to breed near where they were born. Great Crested Flycatchers are monogamous. Young stay with their family group for up to 3 weeks after hatching. Highly active at dawn and dusk. Great Crested Flycatchers likely play a significant role in controlling local insect populations. Like most birds, this species is negatively affected by human activities including pesticide use, man-made structures in migratory pathways, and loss of forests. Click here to listen to its weeeep call. Click here to watch Great Crested Flycatchers add snakeskins to their nest.Great Crested Flycatcher

Fun Facts