A Different Fall on Campus

CONNECTIONS

The Pulse and Politics of the Environment, Peace, and Justice

Bob Musil, President, Rachel Carson Council

“In nature nothing exists alone.”

“The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history… It seems to me, then, that there can be no separate literature of science.”

“If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem.”

— Rachel Carson

08-20-18

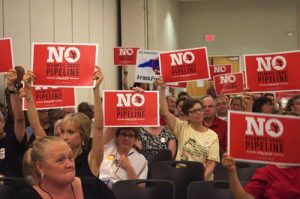

Environmentalists have been playing desperate defense since the 2016 election brought a trifecta of right-wing, anti-environmental, indeed, anti-progressive forces to power — the Trump White House, a reactionary 115th Congress, and a similarly tilting Supreme Court. We have resisted admirably, with broad educational and organizing campaigns, climate and science marches, sit-ins and demonstrations over pipelines, lawsuits against drilling on public lands, and much more.

Our progressive allies, who also see government as a force to protect and promote diplomacy and peace, women’s rights, civil rights, the environment, and to prevent vast income inequality and injustice have also marched, rallied, petitioned, occupied, and tried to generally educate, alert and arouse the public.

Our progressive allies, who also see government as a force to protect and promote diplomacy and peace, women’s rights, civil rights, the environment, and to prevent vast income inequality and injustice have also marched, rallied, petitioned, occupied, and tried to generally educate, alert and arouse the public.

What the election of 2016 has shown activists and advocates — in ways similar to, but even worse than the questionable defeat of Al Gore by George W. Bush in 2000 that led to the Iraq War — is that elections, and whether and how progressives participate in them, have vast consequences, not just for the environment, but for democracy itself. Global climate change, the protection of Americans from toxic chemicals, the heritage of our wilderness and public lands, and the fate of workers and communities of color who live and work in and around our most polluting industries are all on the ballot this fall. So, too, is any possibility of stopping the runaway Trump government from veering further toward increasingly autocratic rule, unless pro-progressive forces control at least one chamber of the U.S. Congress.

Environmentalists and progressives have long believed that demographics and the future are leaning their way with increases in the proportion of young and minority potential voters. But, turn out of the young for elections, rather than rallies, has proved difficult. Even in 2016, for example, despite the hoopla around Bernie Sanders, less than half of eligible voters on college campuses actually cast a ballot, according to the Institute for Democracy in Higher Education at the Jonathan Tisch College of Civics at Tufts University (IDHE). In the mid-term election of 2014, however, only 17% of eligible young voters turned out. If there is to be anything resembling a “wave” election that sweeps away pro-Trump majorities in Congress, environmentalists and their allies will have to do far better in mobilizing campuses for engagement in the mid-term election of 2018, as well as in the future.

The League of Conservation Voters (LCV), the election arm of the environmental movement, has developed a targeted plan to turn out voters in order to capture 25 critical swing Congressional for environmentalist and progressive candidates, while on-campus efforts to engage administrators, faculty, and students in elections are already underway this fall.

This fall on campus, then, will be quite different. Usually, it seems, it has been bucolic, eternal autumn at colleges. They are awash in gold, crimson and orange foliage surrounding Georgian brick or Gothic stone buildings. At least that is how they look on campus websites, view books, and glossy brochures designed to attract prospective students like migrating hawks to a windy ridge. But today those scenes symbolizing the idyllic, isolated, ivory towers of the past are fading. As students return and classes begin, civic engagement beyond the ivied walls is increasingly common at American colleges and universities. This trend has escalated since the advent of the Trump Administration and its allies and their bold attacks on science, the environment, women’s rights, the media, and even higher education itself.

This fall on campus, then, will be quite different. Usually, it seems, it has been bucolic, eternal autumn at colleges. They are awash in gold, crimson and orange foliage surrounding Georgian brick or Gothic stone buildings. At least that is how they look on campus websites, view books, and glossy brochures designed to attract prospective students like migrating hawks to a windy ridge. But today those scenes symbolizing the idyllic, isolated, ivory towers of the past are fading. As students return and classes begin, civic engagement beyond the ivied walls is increasingly common at American colleges and universities. This trend has escalated since the advent of the Trump Administration and its allies and their bold attacks on science, the environment, women’s rights, the media, and even higher education itself.

As fall semester 2018 opens, there are signs academia is stepping up. Harvard University President Larry Bacow, for instance, and over 100 Harvard medical and scientific luminaries, have signed an open letter penned by Harvard Law School professor Wendy Jacobs harshly criticizing the Trump Administration’s new ruling that the EPA will not consider scientific studies for which researchers refused to reveal confidential sources, raw data, and more.

Campus administrators and faculty, as well as students, have felt a growing need to speak out on critical public issues because of President Trump’s failure to condemn far right-wing violence, as in Charlottesville, his racist attacks on members of Congress and his own former staff, his resistance to criticizing Russian interference in U.S. elections, and his deep anti-intellectualism, attacks on science, and belief that climate change is a “hoax.” Even before he took office, 1400 climate change scientists, most at universities, published a public letter calling on the President-elect to accept climate science and take steps to prevent further climate disruption. More recently, 15,000 scientists have signed a renewed, stark warning, written by Oregon State University professor William Ripple, that unless action is taken rapidly, climate change is on track to destroy modern societies.

Nevertheless, such statements and appeals, as admirable as they may be, cannot change U.S. public policy, so long as the Trump White House and the current Congress remain in power.

And so this autumn, campuses, and organizations that work with them, are looking beyond the fall foliage and ivied walls to engage their communities in the 2018 election and the broad civic and political life that provide the only realistic pathways for serious change — whether on race, sound science, the environment, or other critical issues.

Author and activist Paul Loeb, for example, heads the Campus Election Engagement Project (CEEP) that goes far beyond traditional efforts to register students to vote with tables along the paths crossing campus quadrangles. CEEP, which has seen a leap in funding and staff this year, works to embed the importance of voting and political participation through institutional involvement and change. Presidents, deans, provosts, student government, athletic teams and coaches, service learning courses and faculty, and more are involved in creating a non-partisan, but highly engaged culture of voting and participation. In one of many examples cited by CEEP, North Carolina A&T University registered over 12,000 students, staff, faculty, and community members in the last election by combining on-campus registration with service projects where students registered voters on six successive weekends in nearby low-income neighborhoods. The outreach culminated in a rally with live music, food, and voter registration tables.

Techniques encouraged by CEEP include debate watch parties, campus debates, and even courses on elections that include registering voters as service learning. At the University of Kentucky, a journalism professor created a documentary about the importance of the youth vote that broadcast on public television statewide. His journalism class organized around the showing, got campus administrators and student leaders to send out election questions on a school wide app, distributed election-related banners and flyers, tweeted election information, and advertised a mock election. The school newspaper, the Kentucky Kernel, ran the CEEP candidate guide, and the class promoted and attended Lexington’s mayoral debate.

CEEP also hires campus election Fellows to work on individual campuses. In some cases, student governments themselves put funds into election-related efforts. Both the University of Wisconsin-Madison and the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, for example, gave $5,000 to fund CEEP student Fellows who then coordinated nonpartisan election engagement efforts and volunteer teams.

Initiatives to transform campus institutional culture beyond elections have been growing as well. In 2016, the Obama Administration and the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U), which has over 1300 campuses as members, issued a groundbreaking report, A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy’s Future, on the importance for American democracy of democratic engagement in American higher education. Building on that document, the AAC&U has created the Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Action Network that coordinates and highlights the efforts of 13 higher education associations to develop effective civic engagement on college campuses. The Institute for Democratic Engagement (IDHE), meanwhile, has just published Election Imperatives: Ten Recommendations to Increase College Student Voting and Improve Political Learning and Engagement With Democracy. The report is co-sponsored by eleven higher education associations and organizations, including AAC&U, which endorse making elections and civic engagement central to academic life.

Initiatives to transform campus institutional culture beyond elections have been growing as well. In 2016, the Obama Administration and the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U), which has over 1300 campuses as members, issued a groundbreaking report, A Crucible Moment: College Learning and Democracy’s Future, on the importance for American democracy of democratic engagement in American higher education. Building on that document, the AAC&U has created the Civic Learning and Democratic Engagement Action Network that coordinates and highlights the efforts of 13 higher education associations to develop effective civic engagement on college campuses. The Institute for Democratic Engagement (IDHE), meanwhile, has just published Election Imperatives: Ten Recommendations to Increase College Student Voting and Improve Political Learning and Engagement With Democracy. The report is co-sponsored by eleven higher education associations and organizations, including AAC&U, which endorse making elections and civic engagement central to academic life.

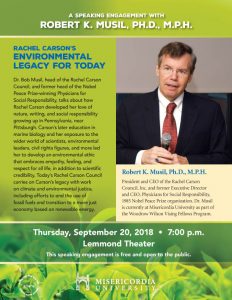

The Rachel Carson Council Campus Network (RCCN), which focuses on the environment and justice, with over 3,000 active faculty, administrators and students at 50 colleges will also highlight the importance of elections and civic engagement this fall. The RCCN is distributing materials from the CEEP and IHDE to its own members nationwide. And, in my own campus speeches, workshops, and classes this fall, (Bennett and Meredith Colleges in North Carolina, Hofstra University on Long Island, and Misericordia University in Pennsylvania) I will be featuring the importance of elections to the work of Rachel Carson herself (Carson actively campaigned for Adlai Stevenson and John F. Kennedy) and to achieving long-range environmental and democratic goals.

The Rachel Carson Council Campus Network (RCCN), which focuses on the environment and justice, with over 3,000 active faculty, administrators and students at 50 colleges will also highlight the importance of elections and civic engagement this fall. The RCCN is distributing materials from the CEEP and IHDE to its own members nationwide. And, in my own campus speeches, workshops, and classes this fall, (Bennett and Meredith Colleges in North Carolina, Hofstra University on Long Island, and Misericordia University in Pennsylvania) I will be featuring the importance of elections to the work of Rachel Carson herself (Carson actively campaigned for Adlai Stevenson and John F. Kennedy) and to achieving long-range environmental and democratic goals.

This autumn there will be plenty of gorgeous foliage on campuses and, of course, some parties and some excitement on the playing fields. But the important action this year — in classrooms, campus clubs, and at those many tables lining shaded walkways – will be around the critical mid-term election of 2018.

This autumn there will be plenty of gorgeous foliage on campuses and, of course, some parties and some excitement on the playing fields. But the important action this year — in classrooms, campus clubs, and at those many tables lining shaded walkways – will be around the critical mid-term election of 2018.