Trump, Rachel Carson, War and the Environment?

CONNECTIONS

The Pulse and Politics of the Environment, Peace, and Justice

Bob Musil, President, Rachel Carson Council

“In nature nothing exists alone.”

“The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history… It seems to me, then, that there can be no separate literature of science.”

“If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem.”

— Rachel Carson

09-19-17

President Trump has casually threatened nuclear war before and now has promised formally in a chilling speech at the United Nations to “totally destroy” North Korea if need be — presumably by using nukes. With North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un continuing to fire off missiles, and with civilians — mostly women and children — the main casualties and refugees in wars across the Middle East, environmental issues like worrying about drilling in the Arctic or building natural gas pipelines can sometimes seem almost trivial. Unless, of course, these seemingly random events are somehow connected. They are. Continued reliance on fossil fuels that causes global climate change threatens fragile ecosystems and the planet, but also exacerbates the conditions — drought, food insecurity, refugee movements, and more — that lurk beneath the violence and war in the world. Rachel Carson linked the dangers of war, nuclear weapons, and environmental destruction to the quest for easy profit and mankind’s arrogance in believing we could control nature.

President Trump has casually threatened nuclear war before and now has promised formally in a chilling speech at the United Nations to “totally destroy” North Korea if need be — presumably by using nukes. With North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un continuing to fire off missiles, and with civilians — mostly women and children — the main casualties and refugees in wars across the Middle East, environmental issues like worrying about drilling in the Arctic or building natural gas pipelines can sometimes seem almost trivial. Unless, of course, these seemingly random events are somehow connected. They are. Continued reliance on fossil fuels that causes global climate change threatens fragile ecosystems and the planet, but also exacerbates the conditions — drought, food insecurity, refugee movements, and more — that lurk beneath the violence and war in the world. Rachel Carson linked the dangers of war, nuclear weapons, and environmental destruction to the quest for easy profit and mankind’s arrogance in believing we could control nature.

Yet the contemporary environmental movement has, with only a few exceptions, almost unanimously failed to connect war and the environment, let alone corporate greed and technological arrogance. The same is also true for the far smaller and scattered remnants of the peace and anti-nuclear movements. Both need to. Unless these and other modern reform movements discover, discuss, and deploy their forces around the connections between war and environmental degradation — and the related effects on poverty, economic and racial inequality, democracy, and human rights — staving off, let alone ending, the horrors of a broken and bleeding planet will prove very difficult indeed, if not impossible.

Yet the contemporary environmental movement has, with only a few exceptions, almost unanimously failed to connect war and the environment, let alone corporate greed and technological arrogance. The same is also true for the far smaller and scattered remnants of the peace and anti-nuclear movements. Both need to. Unless these and other modern reform movements discover, discuss, and deploy their forces around the connections between war and environmental degradation — and the related effects on poverty, economic and racial inequality, democracy, and human rights — staving off, let alone ending, the horrors of a broken and bleeding planet will prove very difficult indeed, if not impossible.

It has not always been this way. During the 1980s, one of the most effective and powerful campaigns was one to block the building and deployment in the American Southwest of 200 mobile intercontinental missiles called the MX. The MX missile, essentially the size of an ancient oak tree, housed 10 separate thermonuclear warheads in its nose cone — each with about 10 times the blast of the Hiroshima atomic bomb. Under a plan approved by the Carter administration that Ronald Reagan attempted to implement, 200 MX missiles were to be mounted on special carriers on railroad tracks running through 4600 shelters intermittently spaced over thousands of miles of track. The idea was the MX train could stop and hide from Soviet missiles.

It has not always been this way. During the 1980s, one of the most effective and powerful campaigns was one to block the building and deployment in the American Southwest of 200 mobile intercontinental missiles called the MX. The MX missile, essentially the size of an ancient oak tree, housed 10 separate thermonuclear warheads in its nose cone — each with about 10 times the blast of the Hiroshima atomic bomb. Under a plan approved by the Carter administration that Ronald Reagan attempted to implement, 200 MX missiles were to be mounted on special carriers on railroad tracks running through 4600 shelters intermittently spaced over thousands of miles of track. The idea was the MX train could stop and hide from Soviet missiles.

The Cold War craziness and vast costs of the MX program quickly brought about strong opposition from and rapid growth for the anti-nuclear movement. National organizations like SANE: The Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy helped lead lobbying campaigns in Washington and sent organizers to Utah and New Mexico where most of the deployment was to be carried out.

Because the construction of this mega-project was centered in the fragile and arid Great Basin ecosystem of the Southwest, peace organizers soon linked up with environmentalists, ranchers, and even the Mormon Church. Broad, cross-issue coalitions voiced concern about endangered species like the desert tortoise, about the vast amounts of water to be used in construction, about grazing lands, about sacred Native American sites, and more. Some rallies literally featured ensembles of cowboys, Indians, anti-nuclear activists, clergy, and members of the Sierra Club.

Because the construction of this mega-project was centered in the fragile and arid Great Basin ecosystem of the Southwest, peace organizers soon linked up with environmentalists, ranchers, and even the Mormon Church. Broad, cross-issue coalitions voiced concern about endangered species like the desert tortoise, about the vast amounts of water to be used in construction, about grazing lands, about sacred Native American sites, and more. Some rallies literally featured ensembles of cowboys, Indians, anti-nuclear activists, clergy, and members of the Sierra Club.

I was with SANE at the time and worked with Michelle Perrault and other western Sierra club activists to help convince the national Sierra Club finally to oppose the MX missile and join forces with the anti-nuclear movement. As the movement continued to grow, other national environmental organizations began to join in anti-nuclear efforts. Green groups were especially active around efforts to close and clean up the sixteen huge nuclear production facilities filled with radioactive wastes. The nuclear weapons complex that employed over 160,000 workers in some 16 secret industrial sites that first produced the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs then went on to build 60,000 additional nuclear bombs. The nuke complex was still manufacturing five nuclear weapons per day under President Reagan.

I was with SANE at the time and worked with Michelle Perrault and other western Sierra club activists to help convince the national Sierra Club finally to oppose the MX missile and join forces with the anti-nuclear movement. As the movement continued to grow, other national environmental organizations began to join in anti-nuclear efforts. Green groups were especially active around efforts to close and clean up the sixteen huge nuclear production facilities filled with radioactive wastes. The nuclear weapons complex that employed over 160,000 workers in some 16 secret industrial sites that first produced the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombs then went on to build 60,000 additional nuclear bombs. The nuke complex was still manufacturing five nuclear weapons per day under President Reagan.

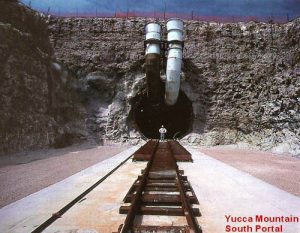

Environmental groups also joined in the campaign to prevent the opening of the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste facility in Nevada. The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), one of the largest and most mainstream environmental organizations, developed a large and sophisticated anti-nuclear program and joined the Plutonium Challenge, a national coalition aimed at nuclear production facilities and nuclear wastes. The Environmental Working Group (EWG), then one of the newer organizations with innovative consumer and environmental health approaches to environmental issues, helped lead the opposition to the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Repository, an underground facility designed to hold nuclear waste. These campaigns finally reduced the MX missile program to 50 stationary sites and eventual elimination, prevented the Yucca Mountain facility from being opened, and shut down the entire nuclear weapons production complex, while gaining billions of dollars for clean-up.

Environmental groups also joined in the campaign to prevent the opening of the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste facility in Nevada. The Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), one of the largest and most mainstream environmental organizations, developed a large and sophisticated anti-nuclear program and joined the Plutonium Challenge, a national coalition aimed at nuclear production facilities and nuclear wastes. The Environmental Working Group (EWG), then one of the newer organizations with innovative consumer and environmental health approaches to environmental issues, helped lead the opposition to the Yucca Mountain Nuclear Repository, an underground facility designed to hold nuclear waste. These campaigns finally reduced the MX missile program to 50 stationary sites and eventual elimination, prevented the Yucca Mountain facility from being opened, and shut down the entire nuclear weapons production complex, while gaining billions of dollars for clean-up.

Nevertheless, the most successful anti-nuclear campaign of all time was, in fact, a combined environmental and human rights one. It was the original, decades-long, global struggle to end the open-air explosive testing of nuclear and thermonuclear weapons. Before they were banned by the Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty of 1963, some 2,000 open-air American and Soviet nuclear tests polluted the atmosphere with radioactive fallout and caused millions of excess cancer deaths around the world. In the United States, only a small minority of journalists, activists, religious figures, and scientists had originally opposed the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yet as the horrific effects of those unprecedented blasts on people, structures, and the landscape became better known, opposition to nuclear weapons began to spread.

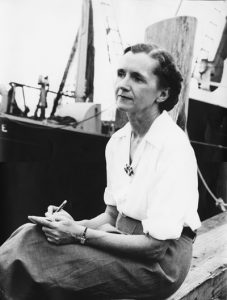

At Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific in 1946, the very first American nuclear tests (Operation Crossroads) exploded two atomic bombs — from the air and from underwater — on surplus Navy ships laden with test animals. The results appalled scientists who studied the effects of blast and radiation on the flora and fauna on and around the target ships. Among them were the noted oceanographer Roger Revelle, who later helped turn attention to global warming, and his friend and colleague — none other than the marine biologist and writer, Rachel Carson.

At Bikini Atoll in the South Pacific in 1946, the very first American nuclear tests (Operation Crossroads) exploded two atomic bombs — from the air and from underwater — on surplus Navy ships laden with test animals. The results appalled scientists who studied the effects of blast and radiation on the flora and fauna on and around the target ships. Among them were the noted oceanographer Roger Revelle, who later helped turn attention to global warming, and his friend and colleague — none other than the marine biologist and writer, Rachel Carson.

Carson, the most acclaimed environmentalist of the twentieth century, never drew distinctions between the horrific effects of nuclear weapons on human beings or plants and animals. She became an immediate and outspoken opponent of nuclear weapons, testing, and waste. She even wrote a new, anti-nuclear Preface to her best-selling 1951 ocean book, The Sea Around Us, for its second, revised 1961 edition — published at the height of the campaign against nuclear weapons and testing. Carson linked the destructiveness of chemicals like DDT and nuclear weapons to the arrogance of humankind — our belief that we stand apart from and can control nature. Carson also joined early anti-nuclear and environmental health activists who believed that the consequences of nuclear testing were also an issue of justice.

Rachel Carson wrote eloquently about the harmful effects on innocent humans far removed from nuclear testing and the power-driven concerns of the United States and the Soviet Union. She described, in scientific detail, how radionuclides from nuclear testing in Nevada reached and affected Inuit mothers in the Arctic Circle. Their breast milk contained radioactive Strontium 90 from fallout that, blown by winds and deposited by rain, moved up the food chain, and finally bioaccumulated in their bodies. Carson also became a friend and ally of Dr. Albert Schweitzer, the most respected international humanitarian of the day. His 1952 Nobel Peace Prize speech denounced nuclear testing and called for a “reverence for life,” an ethic that Carson shared, refusing to categorize or differentiate human beings and other species as less worthy of dignity and respect.

Rachel Carson wrote eloquently about the harmful effects on innocent humans far removed from nuclear testing and the power-driven concerns of the United States and the Soviet Union. She described, in scientific detail, how radionuclides from nuclear testing in Nevada reached and affected Inuit mothers in the Arctic Circle. Their breast milk contained radioactive Strontium 90 from fallout that, blown by winds and deposited by rain, moved up the food chain, and finally bioaccumulated in their bodies. Carson also became a friend and ally of Dr. Albert Schweitzer, the most respected international humanitarian of the day. His 1952 Nobel Peace Prize speech denounced nuclear testing and called for a “reverence for life,” an ethic that Carson shared, refusing to categorize or differentiate human beings and other species as less worthy of dignity and respect.

The global anti-nuclear movement and its links to justice and inequality really took off in 1954 after the death of a Japanese fisherman and the radioactive poisoning of his shipmates aboard the Lucky Dragon — a tuna fishing vessel that was showered with radioactive fallout after the huge American H-bomb test in the Pacific, Castle Bravo. The Lucky Dragon incident, which also caused panic and huge losses in the Japanese tuna industry, occurred just before the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, a summit gathering of non-aligned nations from the developing world who were seeking to create a third way between the capitalist U.S. and communist Soviet Union. The conference denounced nuclear testing and nuclear weapons, linked the nuclear arms race to global inequalities and power, and made leaders like India’s Jawaharlal Nehru international spokespersons for disarmament.

The global anti-nuclear movement and its links to justice and inequality really took off in 1954 after the death of a Japanese fisherman and the radioactive poisoning of his shipmates aboard the Lucky Dragon — a tuna fishing vessel that was showered with radioactive fallout after the huge American H-bomb test in the Pacific, Castle Bravo. The Lucky Dragon incident, which also caused panic and huge losses in the Japanese tuna industry, occurred just before the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, a summit gathering of non-aligned nations from the developing world who were seeking to create a third way between the capitalist U.S. and communist Soviet Union. The conference denounced nuclear testing and nuclear weapons, linked the nuclear arms race to global inequalities and power, and made leaders like India’s Jawaharlal Nehru international spokespersons for disarmament.

In the U.S., Rachel Carson was also friends with, among others, Dr. Barry Commoner. Commoner worked with the Committee on Nuclear Information in St. Louis that measured Strontium 90 in baby teeth, linking distant explosions to immediate family and health concerns. The baby tooth campaign helped to arouse the public, build the movement, and lead to the Limited Test Ban Treaty. Barry Commoner then went on to become a leading environmentalist whose 1971 book, The Closing Circle, urged citizens and scientists to join hands and to link issues like nuclear weapons, the environment, and the economy. It had a major influence on the growth of the environmental movement.

The Vietnam War also sparked some further collaboration between movements, most famously with Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1967 Riverside Church sermon calling for the end of the war and linking its continuation to racial and economic injustice at home. Many groups also denounced the environmental health effects of widespread use of Agent Orange — a powerful herbicide used to clear large areas of jungle in the euphemistically named Operation Ranch Hand. Over 19 million gallons of herbicide, including 11 million gallons of Agent Orange were sprayed over Vietnam. Such toxic effects of warfare, including burning oil wells and depleted uranium munitions, were also noted during the Persian Gulf War and its sequel, the Iraq War. But these concerns were primarily limited to those directly exposed, especially American GIs. Yet the Persian Gulf and Iraq Wars, a number of studies have shown, also have had a variety of serious effects on watersheds and ecosystems, harming fish, shrimp, coral, and other important biota. These and studies of the effects of other wars on the environment are found mostly in scholarly books like Jurgen Brauer’s War and Nature: The Environmental Consequences in a Globalized World.

The Vietnam War also sparked some further collaboration between movements, most famously with Dr. Martin Luther King’s 1967 Riverside Church sermon calling for the end of the war and linking its continuation to racial and economic injustice at home. Many groups also denounced the environmental health effects of widespread use of Agent Orange — a powerful herbicide used to clear large areas of jungle in the euphemistically named Operation Ranch Hand. Over 19 million gallons of herbicide, including 11 million gallons of Agent Orange were sprayed over Vietnam. Such toxic effects of warfare, including burning oil wells and depleted uranium munitions, were also noted during the Persian Gulf War and its sequel, the Iraq War. But these concerns were primarily limited to those directly exposed, especially American GIs. Yet the Persian Gulf and Iraq Wars, a number of studies have shown, also have had a variety of serious effects on watersheds and ecosystems, harming fish, shrimp, coral, and other important biota. These and studies of the effects of other wars on the environment are found mostly in scholarly books like Jurgen Brauer’s War and Nature: The Environmental Consequences in a Globalized World.

However, more recent efforts have been made to discuss and link the environmental and health impacts of war for broader audiences. The environmental effects of war, and preparation for it, are stunningly and credibly laid out, for example, in an award-winning documentary film I was privileged to narrate. Called Scarred Lands, Wounded Lives: The Environmental Footprint of War, its producers are two anti-nuclear, environmental, and population activists, Lincoln and Alice Day. Retired professors and authors of early books on population, the Days were determined to reveal the connections between war and the destruction of the environment. One of Scarred Lands, Wounded Lives’ many convincing segments shows maps and footage of the more than 4,000 World War II naval vessels that were sunk and remain, loaded with fuel and munitions, lying on the ocean bottom, slowly decaying and leaking their toxic contents.

The large contemporary environmental movement is best positioned to engage the public and promote an ecological and human rights stance connecting war and the environment while linking these critical issues to concerns for human health, the rights of women and children, and economic and racial justice. There are already signs that the movement is evolving in this direction. Big Green groups like NRDC and the Sierra Club have developed programs, staff and strong stands on environmental racism. A few Green groups like Earth Justice, Friends of the Earth, and Greenpeace were the first, in varying degrees, to have combined environmental, justice, and peace issues. Science-based groups like the Union of Concerned Scientists and Physicians for Social Responsibility long ago transformed themselves from mainly anti-nuclear groups to organizations to include broader environmental health and justice issues. And, at last year’s Rachel Carson 75th Anniversary Civic Colloquium in Washington, anti-nuclear, environmental racism, and environmental groups collaborated and sought a common agenda. Several of them agreed to send information to their respective memberships on anti-nuclear and environmental issues.

We now face continuing global conflicts, refugee crises, environmental disasters, and global climate change — exacerbated by the reckless bellicosity and reactionary stance of the Trump Administration and its allies and supporters in the Republican-controlled Congress. The time has come for progressive movement groups — especially those engaged in efforts to save the environment, prevent war, mitigate global climate change, and protect civil rights and civil liberties — to combine issues, join forces, and speak and act as one.