The Winter of Our Discontent?

CONNECTIONS

The Pulse and Politics of the Environment, Peace, and Justice

Bob Musil, President, Rachel Carson Council

“In nature nothing exists alone.”

“The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history… It seems to me, then, that there can be no separate literature of science.”

“If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem.”

— Rachel Carson

I enter the C&O Canal on foot at Lock 10 in Cabin John over a flat wooden bridge and a canal lock with ancient, slightly rusted iron mechanical parts and gears. Over the weekend it was in the seventies in Bethesda. It is mid-January, but my scarlet and gold camelias are in bloom, snowdrops are weeks early, a neighbor’s cherry tree has begun to blossom, and birds are chasing each other in ways that look suspiciously lascivious to me.

I enter the C&O Canal on foot at Lock 10 in Cabin John over a flat wooden bridge and a canal lock with ancient, slightly rusted iron mechanical parts and gears. Over the weekend it was in the seventies in Bethesda. It is mid-January, but my scarlet and gold camelias are in bloom, snowdrops are weeks early, a neighbor’s cherry tree has begun to blossom, and birds are chasing each other in ways that look suspiciously lascivious to me.

I make my way slowly up the canal which, near the lock, is dry and filled with grasses. It is near 60 degrees and bright sun puts everything in sharp relief. The Potomac is in view rushing over rocks, but the sounds are blunted by the roar of the 495 Beltway overpass ahead of me and the Cabin John Parkway beyond the canal off to my right.

I make my way slowly up the canal which, near the lock, is dry and filled with grasses. It is near 60 degrees and bright sun puts everything in sharp relief. The Potomac is in view rushing over rocks, but the sounds are blunted by the roar of the 495 Beltway overpass ahead of me and the Cabin John Parkway beyond the canal off to my right.

I ruminate about the devastation caused by cars and highways throughout Washington and the the thinness of the woods that, with the canal, form the 184-mile long National Park saved by the wilderness-loving Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas who marched the entire length with reporters and politicians gasping in his wake to show them the glories I now enjoy. I am still angry, too, that the forthcoming Senate impeachment trial of Donald Trump is unlikely to end with the conviction of a man who has destroyed environmental protection and the fight against climate change, even as he takes us to the brink of war with Iran through the assassination of a foreign leader.

I ruminate about the devastation caused by cars and highways throughout Washington and the the thinness of the woods that, with the canal, form the 184-mile long National Park saved by the wilderness-loving Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas who marched the entire length with reporters and politicians gasping in his wake to show them the glories I now enjoy. I am still angry, too, that the forthcoming Senate impeachment trial of Donald Trump is unlikely to end with the conviction of a man who has destroyed environmental protection and the fight against climate change, even as he takes us to the brink of war with Iran through the assassination of a foreign leader.

Even above the depressing decibels of traffic, the loud, liquid call of a Carolina Wren interrupts my gloom. The call is soon answered from nearby. I focus my binoculars and magnify a pair of the chestnut and tawny, eye-striped, curved-bill, upright-tailed songsters chasing and flitting about in a small tree along the towpath. I watch, somewhat pruriently, wondering when and how wrens mate and how many broods they produce per year.

Even above the depressing decibels of traffic, the loud, liquid call of a Carolina Wren interrupts my gloom. The call is soon answered from nearby. I focus my binoculars and magnify a pair of the chestnut and tawny, eye-striped, curved-bill, upright-tailed songsters chasing and flitting about in a small tree along the towpath. I watch, somewhat pruriently, wondering when and how wrens mate and how many broods they produce per year.

My wrens chase each other off stage, so I turn back to the dry canal. Small groups of sparrows take off from grassy clumps and dive down into small bushes. As I manage to see one or two, I am surprised to see the dark streaks, chocolate chest spots, and longish tails of Song Sparrows. They are one of my favorite birds that in the suburbs are usually on the ground, singly, or in pairs, or seen singing from a low perch a tune whose lyrics birders astoundingly assert say, “Hip, Hip, Hooray, Boys, Spring is Here Again!”

My wrens chase each other off stage, so I turn back to the dry canal. Small groups of sparrows take off from grassy clumps and dive down into small bushes. As I manage to see one or two, I am surprised to see the dark streaks, chocolate chest spots, and longish tails of Song Sparrows. They are one of my favorite birds that in the suburbs are usually on the ground, singly, or in pairs, or seen singing from a low perch a tune whose lyrics birders astoundingly assert say, “Hip, Hip, Hooray, Boys, Spring is Here Again!”

My mood elevates, despite the automotive din, as a few chickadees and titmice arrive to greet me from nearby branches. A bright red cardinal crosses the towpath, tipping a wing to me, looking less tame, freer and wilder than those that snatch safflower seeds from the feeder near my window. I am feeling freer, wilder, less preoccupied, even in a national park inside the Beltway. My shoulders, jaw, neck unclench. I sense, or at least begin to imagine, that out here, where there are scattered rocks and small, dense copses of trees along the canal, I might even see a fox.

My mood elevates, despite the automotive din, as a few chickadees and titmice arrive to greet me from nearby branches. A bright red cardinal crosses the towpath, tipping a wing to me, looking less tame, freer and wilder than those that snatch safflower seeds from the feeder near my window. I am feeling freer, wilder, less preoccupied, even in a national park inside the Beltway. My shoulders, jaw, neck unclench. I sense, or at least begin to imagine, that out here, where there are scattered rocks and small, dense copses of trees along the canal, I might even see a fox.

Then, with binoculars dangling uselessly around my neck, in front of me, a red fox dashes from out of the floodplain trees, across the towpath, the grassy canal, and disappears into some tangled brush. I have no time to regret such a fleeting view as a larger fox follows not far behind. But this one stops in plain view to poke and sniff amidst the grass. I freeze, holding my breath, hoping not to scare off this magnificent russet member — along with wolves and dogs — of the family Canidae.

Then, with binoculars dangling uselessly around my neck, in front of me, a red fox dashes from out of the floodplain trees, across the towpath, the grassy canal, and disappears into some tangled brush. I have no time to regret such a fleeting view as a larger fox follows not far behind. But this one stops in plain view to poke and sniff amidst the grass. I freeze, holding my breath, hoping not to scare off this magnificent russet member — along with wolves and dogs — of the family Canidae.

The noise from the highways seems to keep the fox from hearing me or paying me much attention. I watch it lift its leg and mark its territory on a small clump in the canal that looks like a field now that I have slowly inched my binoculars up to my eyes. I have never communed with a fox like this before. I amble slowly forward just behind, hoping to see it catch a mouse, or vole, or something tasty to a fox. Along with its thick, healthy, slightly red-orange fur, I note carefully its black nose on a white-tipped, pointed face, the black ears that occasionally twitch as if to sense my presence or some prey, the stylish black stockings, the dab of white on the full, bushy tail. Monsieur Renard gazes at me now, unconcerned, perhaps even interested, showing off his lustrous, rufous coat to this human admirer with brown, enlarged eyes at the end of some piece of metal and glass he holds up to his face. My fox wanders forward; I follow in its steps. We pause, exchange glances and move forward together, sharing the rhythms of the day.

Finally, with a farewell glance, my red fox trots calmly across the canal bed and vanishes as easily as a ghost amidst some rocks and tangles and dense foliage that I suspect is where it dens. Our leisurely stroll together, our lovely interspecies dance, is ended. I nod and bow and smile a bit.

With a slight bounce in my step, I walk back to Lock 10, vowing to return tomorrow while winter is still in hiding. When I do, I am riding my old Trek into a gusty headwind that slows me to the speed at which William O. Douglas walked by here. But I have shaken my dark political thoughts, even as the opening, stately ceremonies of Trump’s impeachment trial begin, and the weekend wintry weather forecast threatens to disrupt and shrink an already much-reduced Women’s March come Saturday. I hope to see my fox again, a sort of longing, or biophilia, that is hard to understand. A reunion is far from likely, but I muse that the wind and approaching cold front may at least yield a harvest of some hawks.

As I pedal slowly forward, I am greeted by small clusters of Dark-eyed juncos, the “snowbirds” from the north, who flash their white-striped tails as they loop low across the canal, landing, still in sight, on nearby trees. The sky is bright cerulean with only a few small, scattered clouds. In the stark sunlight, sycamores that line the canal stand out, brilliant white candelabras pointing to the heavens. Their gleaming, sculpted arms are a gift of winter, when leaves have fallen, and what is invisible in lush, prodigal summer is now revealed – river, rocks, lichen, moss, stumps and fallen, rich, rotting logs growing bits of fern.

As I pedal slowly forward, I am greeted by small clusters of Dark-eyed juncos, the “snowbirds” from the north, who flash their white-striped tails as they loop low across the canal, landing, still in sight, on nearby trees. The sky is bright cerulean with only a few small, scattered clouds. In the stark sunlight, sycamores that line the canal stand out, brilliant white candelabras pointing to the heavens. Their gleaming, sculpted arms are a gift of winter, when leaves have fallen, and what is invisible in lush, prodigal summer is now revealed – river, rocks, lichen, moss, stumps and fallen, rich, rotting logs growing bits of fern.

The primeval, wind-swept scene along the river calls up the first explorer of this unnavigable ten-mile stretch of the Potomac between Little Falls and Great Falls. Captain John Smith and his men landed a barge right here in 1608. They trudged in wilderness, dining with Native Americans, taking note of bison, and the small, gray rocky cliffs I see around me.

The primeval, wind-swept scene along the river calls up the first explorer of this unnavigable ten-mile stretch of the Potomac between Little Falls and Great Falls. Captain John Smith and his men landed a barge right here in 1608. They trudged in wilderness, dining with Native Americans, taking note of bison, and the small, gray rocky cliffs I see around me.

I am far past my red fox lair as the canal shows small rivulets amidst grass and mud. A flock of eighty Mallards is now dipping and dabbling at my feet. The drakes proudly show shining heads of emerald green, with cinnamon breasts and orange legs and feet that appear when they stand on their heads to nibble some tidbit beneath the surface.

I am far past my red fox lair as the canal shows small rivulets amidst grass and mud. A flock of eighty Mallards is now dipping and dabbling at my feet. The drakes proudly show shining heads of emerald green, with cinnamon breasts and orange legs and feet that appear when they stand on their heads to nibble some tidbit beneath the surface.

Then comes a smaller bunch of some dozen Mallards, drakes and browner, less conspicuous hens. Two of them look smaller, so I zoom in with binoculars. A pair of Green-winged teals emerges magnified, paddling amidst the Mallards. The male has a distinctive, large oval of green upon a rusty-colored head. Green-wings are distinctive on the fly, tiny colorful crossbows streaking across the sky. But they are beautiful up close in this muddy shallow water with their friendly Mallard cousins.

Then comes a smaller bunch of some dozen Mallards, drakes and browner, less conspicuous hens. Two of them look smaller, so I zoom in with binoculars. A pair of Green-winged teals emerges magnified, paddling amidst the Mallards. The male has a distinctive, large oval of green upon a rusty-colored head. Green-wings are distinctive on the fly, tiny colorful crossbows streaking across the sky. But they are beautiful up close in this muddy shallow water with their friendly Mallard cousins.

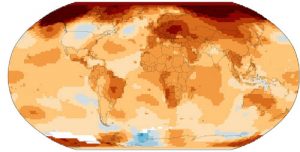

But I am puzzled as, up ahead, I come upon a batch of perhaps twenty plain brown ducks, all resembling female Mallards. They are feeding avidly, rear ends in the air, dabbling and tipping as they cruise around the little pond that is formed inside the canal. I am confused. Some of the female Mallards have black instead of yellow bills, though the feet and legs of all of them are yellow orange. There is a slightly softer, rounder look to the heads of those with black instead of yellow bills. And different colored streaking on their backs as well. Mutants? Hybrid puddle ducks? Pintails without long tails? I try to memorize the black and white patterns toward the back or anything that will help me know who these ersatz Mallards really are. It takes a field guide and some searching to discover that I am watching Gadwalls, ducks I have not seen in many years. Then, in wetlands by the Philadelphia airport, or in preserves along the Jersey shore, I considered Gadwalls to be quite uncommon. But the book tells me that in the last couple of decades, they have been increasing their population. It is a mistake to consult a book while exploring nature. I sense gloom returning as I visualize the 30% decline in North American species since I started birding in the seventies. Images of oil spills, pesticides, rampant development, and the global warming that has now produced a decade of record temperatures, fill my brain.

But I am puzzled as, up ahead, I come upon a batch of perhaps twenty plain brown ducks, all resembling female Mallards. They are feeding avidly, rear ends in the air, dabbling and tipping as they cruise around the little pond that is formed inside the canal. I am confused. Some of the female Mallards have black instead of yellow bills, though the feet and legs of all of them are yellow orange. There is a slightly softer, rounder look to the heads of those with black instead of yellow bills. And different colored streaking on their backs as well. Mutants? Hybrid puddle ducks? Pintails without long tails? I try to memorize the black and white patterns toward the back or anything that will help me know who these ersatz Mallards really are. It takes a field guide and some searching to discover that I am watching Gadwalls, ducks I have not seen in many years. Then, in wetlands by the Philadelphia airport, or in preserves along the Jersey shore, I considered Gadwalls to be quite uncommon. But the book tells me that in the last couple of decades, they have been increasing their population. It is a mistake to consult a book while exploring nature. I sense gloom returning as I visualize the 30% decline in North American species since I started birding in the seventies. Images of oil spills, pesticides, rampant development, and the global warming that has now produced a decade of record temperatures, fill my brain.

I ride more quickly, pushing, breathing hard to shake such thoughts, to feel once more like the exploring John Smith, or Rachel Carson, or Roger Tory Peterson, or others who have trod these paths before me. Soon the sycamores, sun and silence offer solace. I come to Widewater and see basking double-crested cormorants and Canada geese on the small rocky island in the middle of what here looks like a river. As if on cue, a Cooper’s hawk wings across my path into the trees in deadly pursuit of prey. There are small birds nearby on which a Cooper’s might feast, but now I am more taken by wildness, the big rocky shores, the pines, the boulders bathed in lichen and moss that are at my side.

I stop to soak in the beauty of this place, this land. I look up again to the pure azure sky. I am at peace. I breathe deeply of the freshness of the gusting air. I can return now to face the frenzy of political battles that lie ahead. As I slowly turn to go, a distant black bird sails toward me from high among some clouds. As it nears, the sun catches its shimmering white head and tail. A Bald Eagle — once nearly extinguished by DDT — circles effortlessly, majestically above me, some sort of escort, some affirmation, of what can and must be saved.