The Gift of a Cardinal

The Pulse and Politics of the Environment, Peace, and Justice

Bob Musil, President, Rachel Carson Council

“In nature nothing exists alone.”

“The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history… It seems to me, then, that there can be no separate literature of science.”

“If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem.”

— Rachel Carson

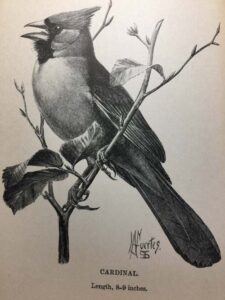

Outside my windows, the morning snow has coated the bushes and branches like a holiday card. Winter birds are everywhere, on the ground, at my feeders, behind holly leaves laden with berries, peeking out, posing for photos to be included in cards and catalogs. There are chickadees, titmice, Downy and Hairy woodpeckers, Carolina wrens, goldfinches, House finches, juncos, White-throated sparrows, Song sparrows, even a robin. A Red-shouldered hawk lands atop my bare tulip poplar. My birds instantaneously disappear. As they return, I focus my binoculars on a brilliant male cardinal — its scarlet body, the black around its bill, its distinguished crest, its elegant, slowly flicking tail. I am struck by its beauty against the white of snow and dark green of holly. Rachel Carson’s words in The Sense of Wonder come to mind, “What if I had never seen this before. What if I knew I would never see it again?”

Outside my windows, the morning snow has coated the bushes and branches like a holiday card. Winter birds are everywhere, on the ground, at my feeders, behind holly leaves laden with berries, peeking out, posing for photos to be included in cards and catalogs. There are chickadees, titmice, Downy and Hairy woodpeckers, Carolina wrens, goldfinches, House finches, juncos, White-throated sparrows, Song sparrows, even a robin. A Red-shouldered hawk lands atop my bare tulip poplar. My birds instantaneously disappear. As they return, I focus my binoculars on a brilliant male cardinal — its scarlet body, the black around its bill, its distinguished crest, its elegant, slowly flicking tail. I am struck by its beauty against the white of snow and dark green of holly. Rachel Carson’s words in The Sense of Wonder come to mind, “What if I had never seen this before. What if I knew I would never see it again?”

Coronavirus precautions have ended my travel, narrowed my physical surroundings, caused me to look to my own backyard for exciting entertainment – some red wine by the firepit, a grandchild laughing through a mask at my antics as a monster or a monkey.

Friends and friends of friends have contracted COVID, a few have died. I still await my vaccine as the virus mutates and spreads more rapidly. A healthy and vigorous senior, I have never before thought much about when, or if, I might die. I try now to take nothing for granted. Even a backyard bird as common as a cardinal. Several gather around and beneath my small, stone St. Francis feeder replete with Francis surrounded by his friends the animals and birds chiseled in deep bas relief. It is filled with small, white safflower seeds, a cardinal favorite. One hovers briefly before alighting on the stone cup. I observe its darker wings as it selects a single seed. It cracks and eats it with the rapid vertical opening and closing of its good-sized beak. Impressed, I imagine trying to eat a nut without lips or teeth.

Friends and friends of friends have contracted COVID, a few have died. I still await my vaccine as the virus mutates and spreads more rapidly. A healthy and vigorous senior, I have never before thought much about when, or if, I might die. I try now to take nothing for granted. Even a backyard bird as common as a cardinal. Several gather around and beneath my small, stone St. Francis feeder replete with Francis surrounded by his friends the animals and birds chiseled in deep bas relief. It is filled with small, white safflower seeds, a cardinal favorite. One hovers briefly before alighting on the stone cup. I observe its darker wings as it selects a single seed. It cracks and eats it with the rapid vertical opening and closing of its good-sized beak. Impressed, I imagine trying to eat a nut without lips or teeth.

A female cardinal waits nearby, perched precariously on the curved, cold, slender rod of a different feeder, as if she were a small, agile sparrow or a finch. To say that the female is brown does her understated beauty a disservice. There is a lovely wash of red with light brown that shades subtly into tawny, buff, sere and cream. There is the crown and beak, the same tail that moves slowly up and down before she flies in a graceful loop onto the snow and seed beneath my nearby azalea.

A female cardinal waits nearby, perched precariously on the curved, cold, slender rod of a different feeder, as if she were a small, agile sparrow or a finch. To say that the female is brown does her understated beauty a disservice. There is a lovely wash of red with light brown that shades subtly into tawny, buff, sere and cream. There is the crown and beak, the same tail that moves slowly up and down before she flies in a graceful loop onto the snow and seed beneath my nearby azalea.

When I was a boy on Long Island long ago, cardinals were not common. We would rush to see them when they visited our yard, a rare gift from the South, a vison almost from the tropics. I still can picture one eating the red, gooey berries on the yew bushes that masked our neighbor’s fence. I look again at the cardinals at my window, longing for the innocence and wonder of my youth.

At another time of plague and less frequent distant travel, the cardinal was seen as extraordinary, not a cliché for cards. It was a symbol of the need to closely observe and appreciate birds and their beauty in our midst. Women writers of the Progressive Era believed our character as a person and as a nation would improve if we learned at a young age to wonder at the nature around us, especially the birds, rather than shoot, collect, or eat them. Gene Stratton Porter, a popular novelist, also wrote books for youth about the birds and nature for just this reason. One of her best-selling works for young people was the novel, The Song of the Cardinal. My own copy is the ninth edition from 1937. As we shift our habits and our gaze because of COVID, I have shared it with my granddaughter, Nora, a precocious, bright, and active eight-year-old who was being driven to distraction by the boredom of her classroom Zooms. “Come here! Come here! Entreats the cardinal,” the hero of the book. A farmer and his wife are exulting that three cardinal babies have hatched. They rush to look because the cardinal has called them, “See here! See here!” But a young hunter has approached, eager to shoot the redbird. Our farmer shames him into stopping and says, “who gave you rights to go ‘round takin’ such beauty an’ joy out of the world?”

At another time of plague and less frequent distant travel, the cardinal was seen as extraordinary, not a cliché for cards. It was a symbol of the need to closely observe and appreciate birds and their beauty in our midst. Women writers of the Progressive Era believed our character as a person and as a nation would improve if we learned at a young age to wonder at the nature around us, especially the birds, rather than shoot, collect, or eat them. Gene Stratton Porter, a popular novelist, also wrote books for youth about the birds and nature for just this reason. One of her best-selling works for young people was the novel, The Song of the Cardinal. My own copy is the ninth edition from 1937. As we shift our habits and our gaze because of COVID, I have shared it with my granddaughter, Nora, a precocious, bright, and active eight-year-old who was being driven to distraction by the boredom of her classroom Zooms. “Come here! Come here! Entreats the cardinal,” the hero of the book. A farmer and his wife are exulting that three cardinal babies have hatched. They rush to look because the cardinal has called them, “See here! See here!” But a young hunter has approached, eager to shoot the redbird. Our farmer shames him into stopping and says, “who gave you rights to go ‘round takin’ such beauty an’ joy out of the world?”

Threats to “collecting” the cardinal because of its beauty are also the concern of Mabel Osgood Wright, another prolific writer of the early twentieth century. Wright created the first bird sanctuary open to the public in her Connecticut home and founded the Connecticut Audubon Society. In Birdcraft: A Field Book of Two Hundred Song, Game and Water Birds, a volume with original drawings by the noted artist, Louis Agassiz Fuertes, designed to interest the emerging suburban middle class in birds and nature, we learn that the cardinal or “cardinal grosbeak,’ was kept as a cage bird because of its delightful singing, especially in England where it was known as the Virginia Nightingale. But it was also shot and killed relentlessly. “The Cardinal owes many of his misfortunes to his ‘fatal gift of beauty.’” It is simply impossible that he should escape notice, and to be seen, in spite of laws to the contrary, means that he will either be trapped, shot, or persecuted out of the country.”

We know that Rachel Carson, and later her friends and colleagues, exposed the dangers of DDT to the reproduction of eagles, ospreys, pelicans and other birds, saving them from extinction. And we know that even as they marched for suffrage, women mobilized to pass the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, saving millions of egrets, herons and other birds from the slaughter of the millinery trade. But to realize that the gentle, gorgeous cardinal, now common even in the North, was endangered, kept caged for amusement, and killed because of its unmistakable scarlet feathers gives new significance to this ordinary backyard bird. Every child can name it. It is festooned, without thought, across pillows and postage stamps, atop the nature paraphernalia that exploits the image of this glorious Virginia Nightingale.

We know that Rachel Carson, and later her friends and colleagues, exposed the dangers of DDT to the reproduction of eagles, ospreys, pelicans and other birds, saving them from extinction. And we know that even as they marched for suffrage, women mobilized to pass the Migratory Bird Treaty Act, saving millions of egrets, herons and other birds from the slaughter of the millinery trade. But to realize that the gentle, gorgeous cardinal, now common even in the North, was endangered, kept caged for amusement, and killed because of its unmistakable scarlet feathers gives new significance to this ordinary backyard bird. Every child can name it. It is festooned, without thought, across pillows and postage stamps, atop the nature paraphernalia that exploits the image of this glorious Virginia Nightingale.

I look again outside my wintry window. A male lands on the sill, just inches from me through the glass. His head is slightly cocked as he peers directly at me. Is he signaling for more safflower seed? Offering thanks? Or simply entreating me with a “Come here! Come here!” to a different, deeper look at our world and the evanescent, fragile beauty that is in it?

The Rachel Carson Council depends on tax-deductible gifts from concerned individuals like you. Please help if you can.

Sign up here to receive the RCC E-News and other RCC newsletters, information and alerts.