Swapping Sea Walls for Salt Marsh? Can Plants Save a North Carolina Island?

Aerial view of living shoreline on Pivers Island in Beaufort, North Carolina, in 2014. Photo Credit: NOAA.

Long marsh grasses fringe the shoreline on Pivers Island, home to NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science and the Duke Marine Lab, in Beaufort, North Carolina. On a calm day, waves lap at the rock sill that frames salt marsh planted along the shore. As waves tumble over the marsh, woody-stemmed plants trap sediment and dissipate wave energy, holding the shoreline together.

The salt marsh around Pivers Island has not always been there—it was planted in the early 2000’s, replacing a degraded bulkhead with a living shoreline. Made of plants, sand, or rock, living shorelines protect and stabilize coastal land using native vegetation and habitats.

“It’s been interesting, you try a whole bunch of stuff and hopefully enough of it catches on and you actually have some change,”

said Dr. Carolyn Currin, an ecologist at NOAA’s lab in Beaufort, North Carolina. Currin proposed the idea for the Pivers Island living shoreline and has been monitoring it over the past two decades.

As the rate of sea level rise and frequency of hurricanes increase in North Carolina, living shorelines have gained recognition as a more effective alternative to hardened structures, such as bulkheads, to prevent erosion. Living shorelines also provide valuable fisheries habitat, reduce eutrophication, improve water quality, and store large amounts of carbon. But despite the proven benefits of these natural buffers, significant barriers remain to their widespread implementation.

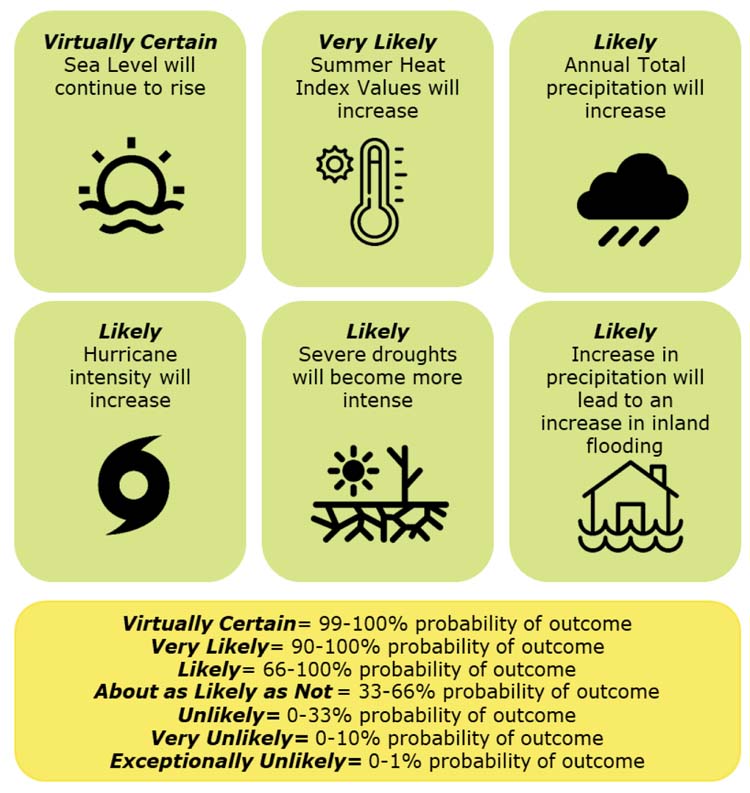

North Carolina Climate Projections. Image credit: North Carolina Climate Risk Assessment and Resilience Plan

In June 2020, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality released its Climate Risk Assessment and Resilience Plan. The plan summarized North Carolina’s climate change projections and proposed recommendations spanning from waste management improvement to the implementation of “nature-based” solutions that could increase coastal resilience and sequester carbon. One nature-based solution recommended was living shorelines.

“I do feel optimistic,” Currin said despite the report’s worrying sea level rise projections.

She noted that the fact North Carolina has a climate resilience plan at all is a step in the right direction. “These are significant positive advances towards dealing with this problem,” Currin said.

The question is whether these recommendations will come to fruition on the ground: “There has been a chasm between reports like this one and the actual rules, policies and laws that work counter to the recommendations,” reported NC Policy Watch.

In the case of living shorelines, the state permitting process is one example of this disconnect.

Five years ago, if homeowners wanted to put in a bulkhead, the bulkhead permit would be approved within 48 hours, while a permit for a living shoreline could take six months.

In 2019, a new general permit streamlined the process for living shorelines.

“It doesn’t fully even the playing field with bulkheads, but it is a big improvement,”

said Carter Smith, a marine conservation scientist at Duke Marine Lab.

Still, while the state continues to permit bulkheads, it may be difficult to promote living shorelines as an alternative. “They want living shorelines to go in the ground and yet they’re still permitting bulkheads,” said Lexia Weaver, a coastal scientist at the NC Coastal Federation Weaver’s goal over the next three years is to work with state agencies to change the permitting policy.

Maryland serves as a model for the coastal management policies that scientists like Weaver are advocating for. In 2008, Maryland passed its Living Shoreline Act, which requires waterfront homeowners to prevent erosion naturally unless they can prove that natural alternatives do not work on their property.

If such a policy change were achieved in North Carolina, a few challenges to living shoreline implementation would remain. Because living shorelines are a new type of infrastructure, there would be an increased need for contractors who are comfortable building them.

Additionally, installing living shorelines is not a “one size fits all” approach. “We don’t have a great understanding of what types of living shorelines to build where,” said Carter Smith of Duke Marine Lab.

One of the biggest challenges to the adoption of living shorelines is changing people’s mindsets.

Historically, armoring shorelines with seawalls or bulkheads has been the common response to coastal erosion. “It’s just what people are used to seeing and doing,” said Weaver of the NC Coastal Federation.

Historically, armoring shorelines with seawalls or bulkheads has been the common response to coastal erosion. “It’s just what people are used to seeing and doing,” said Weaver of the NC Coastal Federation.

In the U.S., 14% of shorelines have been hardened, threatening coastal wetland habitat and accelerating beach erosion rates, according to a 2015 study published in Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment.

Shifting public mindset away from the norm of hardened structures to a more natural approach takes time, advocacy, and communication. Interestingly, neighbors may also be influential. Social scientists found that property owners are more likely to install the type of shoreline modification that their neighbors use, according to a 2020 study in Coastal Management.

“Neighbors have been like a domino effect,” Weaver said. If more waterfront homeowners adopt living shorelines, that could cascade into widespread change in the way shorelines are stabilized—which would be good news for proponents of living shorelines.

“We do have some large federal agencies that are starting build living shorelines. But to a very large extent its small homeowners’ decisions that actually are going to have the biggest impact,” Smith said.

Kendall Jefferys – Rachel Carson Council Presidential Fellow.

Kendall Jefferys – Rachel Carson Council Presidential Fellow.

Kendall Jefferys is a Rachel Carson Scholar at Duke University and a dual major in Environmental Science and English. She initiated the RCC Coasts and Ocean Program. [email protected]

![]() The Rachel Carson Council depends on tax-deductible gifts from concerned individuals like you. Please help if you can.

The Rachel Carson Council depends on tax-deductible gifts from concerned individuals like you. Please help if you can.

![]() Sign up here to receive the RCC E-News and other RCC newsletters, information and alerts.

Sign up here to receive the RCC E-News and other RCC newsletters, information and alerts.