Hood College, Rachel Carson and Environmental Justice

“We might never have heard of Rachel Carson, but for Grace Lippy and Hood College,” RCC President Dr. Bob Musil told his audience at Whitaker Center Commons at Hood College in Frederick, Maryland at the end of February. Musil was hosted by Dr. Paige Eager of the Global Studies Program, and Dr. Sue Carney of the Master’s Program in Environmental Biology. In attendance in the full lecture hall following a dinner in Musil’s honor, were Hood President Andrea Chapdelaine, Provost and Academic Vice President Debbie Ricker, as well as faculty, students and members of the community.

“We might never have heard of Rachel Carson, but for Grace Lippy and Hood College,” RCC President Dr. Bob Musil told his audience at Whitaker Center Commons at Hood College in Frederick, Maryland at the end of February. Musil was hosted by Dr. Paige Eager of the Global Studies Program, and Dr. Sue Carney of the Master’s Program in Environmental Biology. In attendance in the full lecture hall following a dinner in Musil’s honor, were Hood President Andrea Chapdelaine, Provost and Academic Vice President Debbie Ricker, as well as faculty, students and members of the community.

Dr. Musil explained that Grace Lippy, a beloved Hood biology professor who retired in 1967, was Carson’s good friend at Johns Hopkins graduate school where they were in the marine biology doctoral program together during the Depression. Lippy was the only woman hired as an Instructor at Hopkins in the early thirties and made Carson her lab assistant. She accepted a rare Depression-era teaching position at Hood before finishing her Ph.D. Ultimately, Lippy wrote a letter of recommendation for Carson who also needed to stop her Ph.D. work and look for a job because of a lack of funds, family responsibilities, and the paucity of academic jobs for women in science.

Dr. Musil explained that Grace Lippy, a beloved Hood biology professor who retired in 1967, was Carson’s good friend at Johns Hopkins graduate school where they were in the marine biology doctoral program together during the Depression. Lippy was the only woman hired as an Instructor at Hopkins in the early thirties and made Carson her lab assistant. She accepted a rare Depression-era teaching position at Hood before finishing her Ph.D. Ultimately, Lippy wrote a letter of recommendation for Carson who also needed to stop her Ph.D. work and look for a job because of a lack of funds, family responsibilities, and the paucity of academic jobs for women in science.

Rachel Carson, of course, did manage to find a job at the Bureau of Fisheries (later the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) in Baltimore where she embarked on a career in scientific writing and editing that led her to fame as the author of three best-selling ocean books and, finally, Silent Spring. Quoting Hood’s new strategic plan, Musil said that as women in science during the Depression, “Grace Lippy and Rachel Carson were breaking boundaries just as Hood College asks you to do.”

Rachel Carson’s greatest legacy is not Silent Spring, however, Musil said, despite its groundbreaking exposé of the widespread use of pesticides like DDT on both animal and human health and the boost it gave to the modern environment movement. It is, instead, Carson’s environmental ethic — grounded in rigorous science, but infused with a sense of wonder, awe, imagination and empathy for all living things. Without empathy and caring, Carson believed that modern science and the arrogance of humankind that thinks it can control nature is actually dangerous. Such views had in Carson’s time led to the widespread use of dangerous chemicals, as well as the open-air testing of nuclear weapons, the construction of huge, monstrous factory farms, and the beginnings of measurable global climate change. Carson “broke boundaries” and saw such issues as intertwined and as part of an overall mindset that could destroy the planet.

Drawing on Carson’s example and insights, Musil described the RCC’s environmental and climate justice programs today — organizing in both Maryland and North Carolina against factory farms, pipelines and production facilities for natural gas, and the destruction of forests to produce wood pellets for use in power plants in Europe. All these contribute to global warming and harm poor people and communities of color. Rachel Carson did not use the term environmental justice as we do today, Musil explained. Nevertheless, she wrote eloquently, for example, about the plight of Inuit women in the Arctic harmed by radioactivity from far off nuclear weapons testing over which they had no control, or even knowledge. And, she wrote a powerful introduction to the first exposé of factory farms in the 1964 book, Animal Machines, by Ruth Harrison, with deep concern for the animals and humans alike.

Drawing on Carson’s example and insights, Musil described the RCC’s environmental and climate justice programs today — organizing in both Maryland and North Carolina against factory farms, pipelines and production facilities for natural gas, and the destruction of forests to produce wood pellets for use in power plants in Europe. All these contribute to global warming and harm poor people and communities of color. Rachel Carson did not use the term environmental justice as we do today, Musil explained. Nevertheless, she wrote eloquently, for example, about the plight of Inuit women in the Arctic harmed by radioactivity from far off nuclear weapons testing over which they had no control, or even knowledge. And, she wrote a powerful introduction to the first exposé of factory farms in the 1964 book, Animal Machines, by Ruth Harrison, with deep concern for the animals and humans alike.

Describing the effects of the huge poultry industry in Maryland portrayed in the RCC report, Fowl Matters — with some 29,000,000 chickens that produce the same amount of untreated waste as 9.8 million humans — and of climate change, including sea-level rise, flooding, and record rain fall that washes pollutants into the Chesapeake Bay, Musil called on the students and faculty of Hood to join with the Rachel Carson Council to break boundaries, as did Lippy and Carson.

Describing the effects of the huge poultry industry in Maryland portrayed in the RCC report, Fowl Matters — with some 29,000,000 chickens that produce the same amount of untreated waste as 9.8 million humans — and of climate change, including sea-level rise, flooding, and record rain fall that washes pollutants into the Chesapeake Bay, Musil called on the students and faculty of Hood to join with the Rachel Carson Council to break boundaries, as did Lippy and Carson.

Rachel Carson, Musil concluded, was also quite politically engaged. She called on young people in her day to do the same. Musil quoted from Carson’s only full Commencement Address, to the women of Scripps College in California, saying, “your generation must deal with the environment.” That was two generations ago, Musil explained. “Those same words call to us today,” he added. But, given the accelerating climate crisis, “we now must act within the next decade or two. I think I may have a couple of decades left in me to stand and fight alongside you, and I will do that until my final breath. But, in the end, I say with Rachel Carson, it is your generation that must deal with the environment.”

Rachel Carson, Musil concluded, was also quite politically engaged. She called on young people in her day to do the same. Musil quoted from Carson’s only full Commencement Address, to the women of Scripps College in California, saying, “your generation must deal with the environment.” That was two generations ago, Musil explained. “Those same words call to us today,” he added. But, given the accelerating climate crisis, “we now must act within the next decade or two. I think I may have a couple of decades left in me to stand and fight alongside you, and I will do that until my final breath. But, in the end, I say with Rachel Carson, it is your generation that must deal with the environment.”

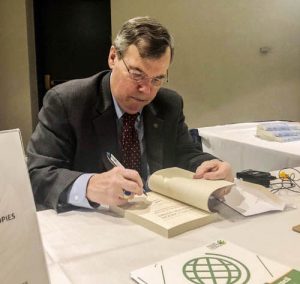

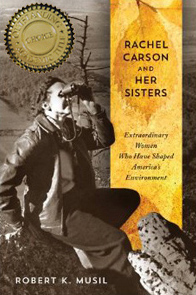

At the end of his speech, Musil signed copies of his book, Rachel Carson and Her Sisters, and met with audience members along with RCC staff Maggie Cummings, Maryland Representative, and Mackay Pierce, Campus Coordinator, to talk about RCC’s new campus Fellows program, its upcoming Fall lobby day, and opportunities for civic engagement with the RCC in Maryland. Following Musil’s visit, Hood College became the 52nd college to join the Rachel Carson Campus Network.