Get Your Boats Ready! Why the U.S. Should Care About Climate Migrants

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that there will be 1.2 billion climate refugees in the world by the year 2050.

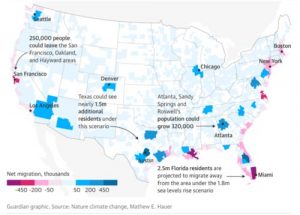

Believe it or not, Americans will be a significant portion of this 200 million, coming from coastal regions in the U.S. such as New Jersey, South Carolina, North Carolina, Florida, Texas, Georgia, and Alaska, among others. According to the Business Insider, these will be some of the first areas to experience increased flooding from sea-level rise with 30 coastal cities going underwater by 2060. The nation is looking at approximately 13 million forced migrants and 311,000 homes that will face floods and become uninhabitable within the next 30 years.

In other words, the climate refugee problem is no longer something you read about only in the international news section of your newspaper. It is happening on our doorsteps. Homes, offices, and property will be destroyed and American residents, while not necessarily refugees, will most likely be classified as forced migrants, or internally displaced people, needing to relocate to safer areas for refuge and rehabilitation.

It is important to note that this outcome is not just a future possibility. A number of cases of climate displacement in the U.S. have arisen since after the first notable migration caused by Hurricane Katrina in 2005. The most publicized occurrence of flooding from sea-level rise is the case in 2016 of Isle de Jean Charles, Louisiana. But hurricanes like Florence on the East Coast have combined damage and displacement from both flooding and winds. “Over the past year, America experienced 11 billion-dollar weather and climate-related disasters. Wildfires in the West, drought in the Midwest and hurricanes in the South forced many thousands of American families to leave their homes in search of safety. Some estimates put that number as high as 1.5 million Americans having migrated in the face of such disasters, temporarily or permanently, to other parts of the country in 2017 alone.”

86% of areas in the U.S. with an urban center including over 10,000 people will be affected by net migration due to sea-level rise.

As shocking as recent American climate disasters have proven to be, it is true that the U.S., along with other richer, developed countries, will not be as severely affected by sea-level rise as less developed nations. Americans have been slow to connect climate change and natural disasters. But, as the climate migrant problem increases here in the U.S., Americans may increasingly come to recognize that on the other side of the world, entire countries and continents are at high risk of complete inundation. Large parts of Haiti, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and several islands nations are only a few names on the top of the hit list compiled in the Global Climate Risk Index.

Climate change has already begun to force large migration around the world. It will continue to do so — further multiplying existing problems in vulnerable parts of Central America, Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Latin America, particularly threats such as poverty and violence. While blame games are rarely productive, it is important to note that as awareness of the climate refugee crisis becomes greater in the U.S., Americans will need to appreciate their responsibility to help abroad as well as at home.

We are significantly responsible for much of the aggravation of existing climate threats in other countries. The United States not only continues to be one of the highest annual contributors of greenhouse gases causing global climate change today; we have produced the largest single total of greenhouses gases pumped into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution began — around 1750. While countries like China and India have overtaken the U.S. in annual carbon emissions in the past decade, given the billion-plus populations of China and India, the U.S. continues to have the highest per capita carbon contribution in the world.

As a result, smaller, more vulnerable countries, and many developing nations that contribute far less to climate change — like Haiti, Myanmar, or Bangladesh — are paying a disproportionately high price from the industrialization of richer nations with none of the benefits. The United States has benefited disproportionately from unsustainable practices, especially with our rapid development after World War II. Given our contribution to global climate problems, it seems only fair and responsible that Americans see our own growing climate disasters and forced migrant problems as only a part of a worldwide crisis that we should take leadership in attempting to solve.

As the number of predicted climate migrants, both globally and in the U.S., increases, Americans can no longer remain uninvolved or ignore this issue. Displaced people both within the United States and across the globe will need new homes and resources for resettlement. National borders, food systems, global economies, and national security will all face incredible stress.

These strains will directly affect us and risk stoking nationalist, even racist fears. But, it is a misplaced notion that granting foreign aid to suffering nations or admitting forced migrants and refugees to the U.S. are merely charitable and humanitarian efforts made at the nation’s and taxpayers’ expense. Contrary to popular belief, the forced migration of the global population is not necessarily disadvantageous for Americans — it can be a real asset for the country if managed properly. The narrative of foreigners stealing American jobs or harming the U.S. economy ignores several important facts regarding the monetary contributions of immigrants to the United States. In reality, the U.S. actually needs immigrants for the country to maintain and improve its economy.

It is still too little understood that immigrants are some of the largest tax-paying communities in the United States. In 2017, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine published a report on the positive financial impact of immigrants on the economy through tax contributions. It found that “second generation immigrants are ‘among the strongest fiscal and economic contributors in the U.S.’ … They contribute about $1,700 per person per year. All other native-born Americans, including third generation immigrants, contribute $1,300 per year on average.” Additionally, the Institute on Taxation & Economic Policy found that undocumented immigrants pay $11.74 billion a year in taxes to the U.S. government. This means that a significant portion of amenities available to the American public, regardless of immigration status, is paid for by immigrant taxpayers. Even international, impermanent residents in the United States pay taxes to the American government for the duration of their residency.

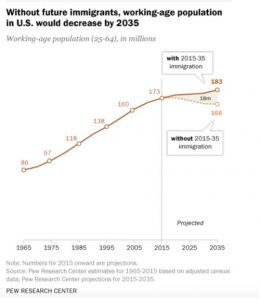

Furthermore, immigrants help maintain the youth population of the United States. Without it, the American economy may face a decline similar to that of Japan. “Japan has a demographic disaster as a result of a low birthrate – the fifth-lowest in the world – and almost no immigration to speak of, with a foreign-born population of only 1.6 percent. Japan is unable to replenish its workforce, and its society is aging rapidly.” Immigrants are some of the youngest populations in the States, and without them, the U.S. economy would resemble Japan’s — great infrastructure, but experiencing a rapid decline without a working class.

“According to the World Bank, the 25 richest countries in the world have an average foreign-born population of 22.5 percent, including the United States (12.8 percent), Hong Kong (42.6 percent), Australia (19.9 percent), and Switzerland (22.9 percent). Conversely, some of the world’s poorest countries are also the most hostile to immigration, like North Korea (0.2 percent foreign-born), Iran (2.9 percent), and Venezuela (3.7 percent).” Ideally, the goal is to reduce global climate change and promote sustainable practices that allow people to stay in their own countries and homes rather than be forced into migration.

However, the U.S. must remain open to a more inclusive immigration policy due to its complicity in global warming and sea-level rise that is causing forced migration, as well as because of the demonstrated benefits of immigration to the American economy.

Nevertheless, American treatment of climate victims and forced migrants has failed to appreciate the value of immigrants of all kinds. Worse, it has treated victims of climate disasters with disdain and disrespect including immigrants, both legal and undocumented, from Central America via Mexico as demonstrated by the inhumane conditions of those seeking asylum along the Southwestern border. There, the situation for external refugees, asylum seekers, and other forced migrants includes detention centers, inhumane treatment, abuse, lack of legal aid, and a complete breakdown of the judicial system that is overwhelmed by the immigration caseload in the country.

Even within the United States itself, Americans displaced by sea-level rise and flooding have been treated shamefully. The Isle de Jean Charles in Louisiana is a prime example of poor migration policy and management in the U.S. The Isle has lost 98 percent of its land due to rising sea levels; what once used to be 22,000 acres is now a mere 300 acres. The Office of Community Development won close to $50 million to relocate the families on the Isle.

However, the tribe members that live there were repeatedly offended by the way decisions regarding resettlement were made without their agreement; many have refused the government grant. Louisiana OCD moved ahead with purchasing resettlement land for the residents of the Isle, ignoring the letter the tribe’s Chief Naquin sent outlining serious concerns, including losing ownership rights to their homes and a lack of insurance. With the recent Hurricane Barry in Louisiana, additional residents of Isle de Jean Charles have been evacuated. Currently, there is no information about the progress of the resettlement plans. After three years since the grant was won, new housing is yet to be built. Furthermore, the temporary housing provided by the OCD, which the authorities call hotels, are known by the victims to be homeless shelters in Houma, a city on the mainland of Louisiana.

In short, America has a migration and displacement problem that will only be exacerbated by climate change and sea-level rise at home and around the globe. It is a crisis that calls for an urgent response to climate change and its disasters from American citizens and the U.S. government, as well as support for nations with large numbers of climate migrants already suffering from historic American carbon emissions. Ignoring the real issues or criminalizing immigrants will cement a future with more humanitarian crises, expensive disaster management, and a declining economy. Alternatively, the United States can treat the influx of people — that is imminent at the current rate of climate change — as an opportunity to create a dignified process of relocation, thus securing the country’s position as an economic and moral superpower in the decades to come.

— Ananya Gupta is a senior pursuing a BA in Environmental Studies (Honors) and English at Oberlin College. She is Managing Editor of The Oberlin Review. 08-08-19