The Ecosystem of the Oval Office

CONNECTIONS

The Pulse and Politics of the Environment, Peace, and Justice

Bob Musil, President, Rachel Carson Council

“In nature nothing exists alone.”

“The aim of science is to discover and illuminate truth. And that, I take it, is the aim of literature, whether biography or history… It seems to me, then, that there can be no separate literature of science.”

“If the Bill of Rights contains no guarantee that a citizen shall be secure against lethal poisons distributed either by private individuals or by public officials, it is surely only because our forefathers, despite their considerable wisdom and foresight, could conceive of no such problem.”

— Rachel Carson

03-10-16

As an ecologist, I look for the interconnection of things. The smallest changes can signal shifts in the rhythms, the realities of life around us. The slow, inexorable movement northward over the twentieth century of the black vulture, once an entirely southern bird, reveals the onset of global climate change. The black vulture, unrecorded in Washington by nineteenth century naturalist writers like John Burroughs, Elliott Coues, and even Teddy Roosevelt, is now common at the National Zoo, along the C&O Canal, and over the White House. In Washington in Spring, I noted the shift in ecosystems around the capital area and wrote, “Scary bird, indeed.” Close observation and study of the tiniest things, like algae in a pond, or mercury in fish, can help us understand the health of an entire system.

That is why early reports in Time magazine of the disappearance of the bust of Martin Luther King, Jr. from the Oval Office when Donald Trump moved in and redecorated caused such a kerfuffle. The mistaken report was based on news photos in which the King bust had been blocked by a door and a photographer standing in front of it. Time corrected the report and apologized. Nevertheless, other details of the new Oval Office décor are accurate.

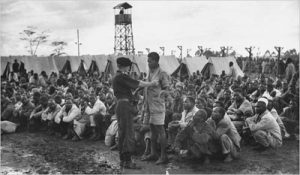

President Trump has introduced some new features, some new species, into the ecosystem of the presidential office. Freshly placed in plain view is a bust of the British Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill. This is chilling enough given Churchill’s bellicosity that led to the needless slaughter of British troops at Gallipoli in World War I. Yet Churchill also happily fought in imperial wars himself, bragging that he had killed “savages” in the Sudan, and that he had fought in “a lot of jolly little wars against barbarous peoples.” He later defended concentration camps in South Africa, writing only of “his irritation that kaffirs should be allowed to fire on white men.”

Mr. Trump can be perhaps be forgiven for failing to keep up on serious history books like Richard Toye’s Churchill’s Empire. But, he seems not to be keeping up with films, either. Set in the forties and fifties, A United Kingdom, tells the true story of the King of Botswana (colonial Bechuanaland), Seretse Khama, played by David Oyelowo. While still a Prince, he has married a white, British woman, Ruth Williams, played by Rosamund Pike. In an ultimately failed attempt to keep this interracial couple from taking the throne, Churchill orders Khama into permanent exile from his country in order not to offend neighboring white-ruled, apartheid South Africa and to maintain access to its mineral wealth.

This same Winston Churchill was Prime Minister while President Barack Obama’s Kenyan grandfather, Hussein Onyango Obama, was held without trial for two years and tortured under suspicion of resisting the empire. It was President Obama who originally removed the Churchill bust introduced to the Oval Office by George W. Bush. Its return by Donald Trump simultaneously signals a snub of a biracial President, a dangerous ignorance of history, and an affirmation of the worst of the racist and colonial past.

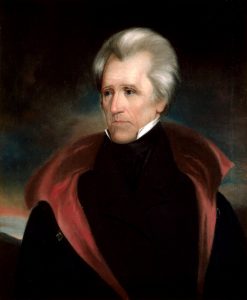

Perhaps Mr. Trump was simply showing his disdain for his predecessor and his policies, not a love of imperial ventures and racism. However, there is yet another detail to notice — the proud, careful, and central introduction into the Oval Office of the portrait of President Andrew Jackson. Trump’s team and his favorite source, Breitbart News, had already touted Trump’s electoral college victory as a reenactment of Jackson’s victory over the Washington “elites” and a return to the era of “the common man.”

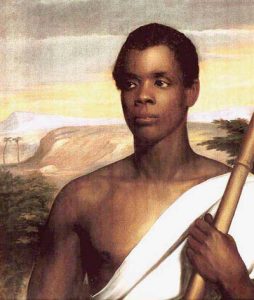

There can be no doubt of the significance of finding this introduced portrait in the ecology of the Oval Office. More recent historical understandings of Jackson had already made him so controversial a figure as to have him soon to be replaced on the face of the twenty-dollar bill by abolitionist and Underground Railroad hero Harriet Tubman. President Jackson ordered the forced removal of the Cherokee Nation in the now infamous Trail of Tears. His victory at the Battle of New Orleans at the close of the War of 1812 was in the interest of those who wanted to expand slavery into new territory. Perhaps most importantly, his victory in 1828 over President John Quincy Adams brought the slave power back into control of the White House. Jackson praised and tried to expand slavery, and instituted tariffs that harmed the manufacturing North and favored the slave South, exacerbating tensions and stoking sectionalism and, ultimately, secession. As it turns out, the vanquished John Quincy Adams and his father, President John Adams, were the only two Presidents of our first twelve occupants of the Oval Office who did not personally own slaves and were opposed to slavery. Quincy Adams went on, however, after losing to Jackson, to return to the pro-slavery House of Representatives. There he tirelessly fought the congressional gag rule barring anti-slavery petitions from consideration. His eloquent defense that freed Cinqué and his followers who had killed white crew members in taking control of the slave ship, La Amistad, remains a proud moment in American history. Again, President Trump may not have read the latest biography of John Quincy Adams But he could have downloaded the Steven Spielberg classic film, Amistad. and watched Anthony Hopkin’s fine rendition of Adams’ moving summation before the Supreme Court.

John Quincy Adams’ support for the Amistad crew grew out of years of close observation of foreign cultures, customs, and languages as one of our nation’s finest diplomats. He could understand and feel that these strangers were indeed fellow humans worthy of respect and freedom. The true story of Cinqué that saved his band of heroic freedom fighters emerged because scholars at Yale and the Connecticut Congregationalists, who housed and helped the Amistad rebels, had listened to and carefully observed what these unjustly captured and arraigned people were saying. Believing in the worth of all individuals, they located a scholar of languages to translate the words of these otherwise seemingly exotic, perhaps even dangerous men. They were of the Mende people from what is now Sierra Leone in West Africa. Their story was true. They had, indeed, been illegally captured and were being dragged off into slavery when they revolted and killed their captors.

Ecologists, naturalists, careful observers of the smallest details of life, learn to care for all the species around them, to see their inherent worth as part of an interconnected web, to love and protect their fellow creatures, their fellow humans. The concept of the dreaded “other,” notions of difference and disdain, of fear and loathing, even hatred, start to fade.

When young, I had never liked vultures of any kind, those ugly creatures who peck and pull at road kill. It took much looking, observing, learning about these splendid scavengers before I could write a short, sort of ode to one in Washington in Spring. I had come upon a black vulture, basking, wings spread wide in golden sunlight, along the C&O Canal:

There are shades of color on its back that I have never seen amidst the shining ebony. Subtle browns and copper and charcoal gray glint against the black. Its feathered wingtips are spread out, each one with six long, shimmering, separated feathers that reflect the steady sunlight to our rear. It was buzzards that Mary Austin celebrated when writing of scavengers out in the western desert. This woodland vulture near me deserves my new respect. It cleans up after all the predators out here who leave behind remains to rot. But because it lives upon such fetid, horrid stuff, soars high above the dead, we revile vultures of all kinds. I stand and briefly try to worship alongside this grand and glorious bird. I spread my arms in kinship and glance upward toward the sky.

There are shades of color on its back that I have never seen amidst the shining ebony. Subtle browns and copper and charcoal gray glint against the black. Its feathered wingtips are spread out, each one with six long, shimmering, separated feathers that reflect the steady sunlight to our rear. It was buzzards that Mary Austin celebrated when writing of scavengers out in the western desert. This woodland vulture near me deserves my new respect. It cleans up after all the predators out here who leave behind remains to rot. But because it lives upon such fetid, horrid stuff, soars high above the dead, we revile vultures of all kinds. I stand and briefly try to worship alongside this grand and glorious bird. I spread my arms in kinship and glance upward toward the sky.

I imagine a different set of details now in the ecology of the Oval Office. Donald Trump has strolled quietly along the C&O Canal, listened, breathed, observed, felt for the different creatures all about him. Then, far into the night, he has poured over piles of books, watched and rewatched films that lovingly present people far distant, far different from himself. The bust of Churchill has been replaced by one of John Quincy Adams. And, more visible, more central, in place of Andrew Jackson, proudly hangs a portrait of Cinqué, born Sengbe Pieh, of the Mende people.