Colleges and Other Institutions Can Change the Food System

Food is at the center of almost every complex social-ecological problem facing the United States today. How we decide to grow, process, distribute, consume, and waste food affects numerous pressing issues: from food security, to chronic diet-related illnesses, to environmental justice and climate change. In the wake of the unforeseen global pandemic, the systems that govern food production and supply chains have proved unreliable for providing our most basic social foundations within the planet’s limits.

Food is at the center of almost every complex social-ecological problem facing the United States today. How we decide to grow, process, distribute, consume, and waste food affects numerous pressing issues: from food security, to chronic diet-related illnesses, to environmental justice and climate change. In the wake of the unforeseen global pandemic, the systems that govern food production and supply chains have proved unreliable for providing our most basic social foundations within the planet’s limits.

How did food go from being the solution to being the root problem? Our food system’s social and environmental burden is largely due to the industrialization of agriculture over the latter half of the 20th century. Due to market pressures from corporate capitalism, a majority of US farmers were forced to abandon small diversified farming systems in favor of specialized, consolidated and standardized operations that isolate animal and crop production. This massive shift led to greater reliance on products from outside farms and subsequent waste production.

How did food go from being the solution to being the root problem? Our food system’s social and environmental burden is largely due to the industrialization of agriculture over the latter half of the 20th century. Due to market pressures from corporate capitalism, a majority of US farmers were forced to abandon small diversified farming systems in favor of specialized, consolidated and standardized operations that isolate animal and crop production. This massive shift led to greater reliance on products from outside farms and subsequent waste production.

Food has the power to be a solution, but presently accounts for a quarter of US greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, with agriculture alone contributing 10 percent. The animal farming industry makes up two-thirds of all agricultural GHG emissions, and exacerbates food-related chronic disease and obesity. 15 percent of Americans live in food insecure households, or 1 in 6 households, and our food insecurity directly costs the US healthcare system 155 billon dollars in spending every year.

Food is arguably the most personal connection between climate issues and human health. Yet, our industrialized system severs this connection, worsens health, and distances us from where, how, and by whom our food is grown. Over the past months, while walking sparsely-stocked grocery store aisles, or by starting gardens in our own backyards, many of us have experienced personal disruption to our food supply chains: From individuals to institutions, our society is realizing the need for a shift from an easily disrupted system, towards a locally-based, resilient system characterized by agricultural diversity, equitable health, and justice.

Food is arguably the most personal connection between climate issues and human health. Yet, our industrialized system severs this connection, worsens health, and distances us from where, how, and by whom our food is grown. Over the past months, while walking sparsely-stocked grocery store aisles, or by starting gardens in our own backyards, many of us have experienced personal disruption to our food supply chains: From individuals to institutions, our society is realizing the need for a shift from an easily disrupted system, towards a locally-based, resilient system characterized by agricultural diversity, equitable health, and justice.

Governmental policies and subsidies can play an important role in effectively changing food systems, but they have not shifted food culture fast enough toward more healthy and sustainable practices. Corporations with hefty purchasing power therefore must be pressured to play redefine standards for food, from production to procurement to consumption. Without grassroots movements and activism targeted at institutions to champion change, progress towards a healed food system is not possible.

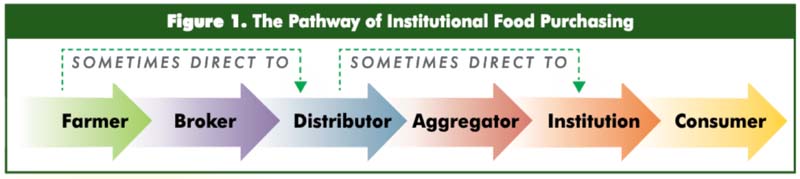

According to a report by the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, just three corporations control 45 percent of the businesses managing dining services in universities, corporate offices, hospitals, prisons, and other institutions. Food distribution is even more consolidated, with Sysco and US Foods taking up an estimated 75 percent of the national market for food distribution. Over 8 billion dollars and 25 percent of the annual revenue of Aramark, Compass Group, and Sodexo is derived from colleges and universities.

According to a report by the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future, just three corporations control 45 percent of the businesses managing dining services in universities, corporate offices, hospitals, prisons, and other institutions. Food distribution is even more consolidated, with Sysco and US Foods taking up an estimated 75 percent of the national market for food distribution. Over 8 billion dollars and 25 percent of the annual revenue of Aramark, Compass Group, and Sodexo is derived from colleges and universities.

In the midst of all this, universities emerge as key “anchor institutions,” with both large-scale purchasing power and meaningful connections in their surrounding community. Anchor institutions are uniquely valuable because they can serve as respected leaders for setting higher food and agriculture standards that establish best practices for others while accelerating market-based changes that individuals would not be able to make on their own. Further, because of campuses’ relatively high buying power and greater likelihood of having fully-equipped kitchens and menu flexibility, colleges possess greater capacity to procure food locally than other institutions which lack these characteristics.

In the midst of all this, universities emerge as key “anchor institutions,” with both large-scale purchasing power and meaningful connections in their surrounding community. Anchor institutions are uniquely valuable because they can serve as respected leaders for setting higher food and agriculture standards that establish best practices for others while accelerating market-based changes that individuals would not be able to make on their own. Further, because of campuses’ relatively high buying power and greater likelihood of having fully-equipped kitchens and menu flexibility, colleges possess greater capacity to procure food locally than other institutions which lack these characteristics.

Upon graduating from high school and entering working life or college, young adults experience substantial life-changing transitions. Being a young adult in college is a critical period for determining individuals’ lifelong health and food choices. Some studies even suggest that those who attend college tend to gain more weight than those who do not. Colleges and universities hold a powerful and unique position with the ability to positively influence and expand students’ eating habits, educate young leaders on the link between university systems and local agriculture, introduce young eaters to local foods, and cultivate an appreciation and understanding of the labor and land required to produce food.

Universities are havens for ingenuity and innovation, charged with developing tomorrow’s leaders. But does the food universities feed their students reflect this? Many students say no.

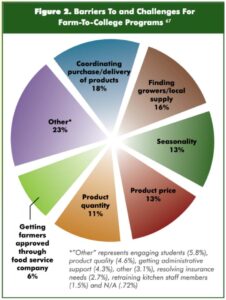

Student-led campaigns and initiatives are emerging across the US to demand higher standards: more plant-based and whole food options, increased local partnerships and sourcing, lower environmental carbon “foodprints,” and higher labor standards for food workers at every link in the supply chain. Initiatives and campaigns such as Menus for Change, DefaultVeg, Real Food Challenge, and Cool Food Pledge are leveraging student ambassadors to put pressure on university administrators and effect change.

Student-led campaigns and initiatives are emerging across the US to demand higher standards: more plant-based and whole food options, increased local partnerships and sourcing, lower environmental carbon “foodprints,” and higher labor standards for food workers at every link in the supply chain. Initiatives and campaigns such as Menus for Change, DefaultVeg, Real Food Challenge, and Cool Food Pledge are leveraging student ambassadors to put pressure on university administrators and effect change.

Advocacy organizations such as Farm to Institution New England, Center for a Livable Future at John Hopkins, World Resources Institute, and The Center for Good Food Purchasing, are mobilizing to develop lifted standards for institutional purchasing. The Center for Good Food Purchasing articulates five key values when evaluating an institution’s procurement: (1) local economics, (2) nutrition, (3) animal welfare, (4) valued workforce, and (5) environmental sustainability. 53 institutions around the country have adopted the metric based Good Food Program framework, by meeting the baseline requirements in each value category and commitment to continued goal-setting, progress reporting, and transparency. The Real Food Challenge defines similar standards with categories: (1) local & community based (2) fair (3) humane (4) ecologically sound.

Compass Group, and its most notable subsidiary group, Bon Appetit Management Company, stands out as a leader in the food service industry, by raising animal welfare standards. Over the past years, the company has committed to purchasing 100% cage free eggs, eliminating pork and veal from animals confined in crates, and doubling the amount of humanely-raised animal products, all certified by third-party auditing systems.

On many campuses, addressing institutional procurement is also being paired with campus gardens or greenhouses where students have the opportunity to both see how food is grown and participate in its production. The experiential piece of gardening and connecting with how food is grown, is powerful. Stepping into a garden asks us to reevaluate how we understand our human needs intersecting with nature’s processes.

Simply picking up a shovel or putting on a pair of gardening gloves becomes a transformational act of reclaiming a connection with how food is grown and defying lengthy distribution chains and resource scarcity.

Stepping onto the farm at my own university was one of my first times on a farm in my life. To connect experiences harvesting broccoli and spinach with seeing labeled dining hall ingredients “from the Furman farm,” prompted me to wonder where all the other food I consume was grown.

Students and faculty at Harvard University have also realized the need for change and explicit commitments, by recently signing on to the Cool Food Pledge to decrease food-related emissions by 25% before 2030. In April 2019, they also released Sustainable and Healthful Food Standards to articulate values and goals for how the university engages with food.

Universities can lay a thoughtful foundation for students’ life-long food purchasing decisions and utilize their immense purchasing power to uplift local farms, support sustainable agriculture, and accelerate food policy.

The pandemic has exacerbated many hurdles to greater sustainability in food service, yet there has never been a more crucial moment for supporting local farms and good purchasing. Moving towards a resilient food system will require our institutions to prioritize meaningful partnerships and relationships, paired with good infrastructure and accountability.

Elise Dudley – RCC Fellow, Furman University

Elise Dudley – RCC Fellow, Furman University

Elise is an RCC Fellow and a Senior Sustainability Sciences student at Furman University. Elise aspires to pursue a career that integrates concerns for climate action, urban design, and public health for building regenerative food systems designed for circularity, justice, and ecosystem diversity. She is currently working as an Undergraduate Research Fellow on backyard gardening as a pathway towards more resilient urban foodscapes.

![]() The Rachel Carson Council depends on tax-deductible gifts from concerned individuals like you. Please help if you can.

The Rachel Carson Council depends on tax-deductible gifts from concerned individuals like you. Please help if you can.

![]() Sign up here to receive the RCC E-News and other RCC newsletters, information and alerts.

Sign up here to receive the RCC E-News and other RCC newsletters, information and alerts.