Rachel Carson and Hawk Mountain

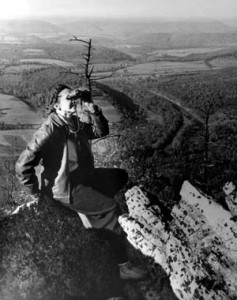

It is a glorious October day, sunny and warm, that has drawn me to hike up three-quarters of a mile along stony paths through woods to the North Lookout of the Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Kempton, Pennsylvania. I sit surrounded by expert research biologists, birders, and school children who outnumber the passing hawks. It is exactly seventy years since Rachel Carson also sat in this very spot amongst the rocks searching for hawks with her good friend and colleague, Shirley Briggs. Shirley and Rachel worked together at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington, D.C. It is Shirley who, in October 1945, took the now iconic photo of Carson, in a stylish leather jacket and slacks, seated on a slab of ancient limestone, peering out through her binoculars at a distant ridge where northwesterly winds aid hawks and eagles and falcons on their fall migrations to the south.

It is a glorious October day, sunny and warm, that has drawn me to hike up three-quarters of a mile along stony paths through woods to the North Lookout of the Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in Kempton, Pennsylvania. I sit surrounded by expert research biologists, birders, and school children who outnumber the passing hawks. It is exactly seventy years since Rachel Carson also sat in this very spot amongst the rocks searching for hawks with her good friend and colleague, Shirley Briggs. Shirley and Rachel worked together at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Washington, D.C. It is Shirley who, in October 1945, took the now iconic photo of Carson, in a stylish leather jacket and slacks, seated on a slab of ancient limestone, peering out through her binoculars at a distant ridge where northwesterly winds aid hawks and eagles and falcons on their fall migrations to the south.

Had Rachel Carson come to Hawk Mountain just over a decade earlier she would have been witness to the annual autumn slaughter of many of the 20,000 or so raptors that now pass by each year. The Visitor Center below features huge enlarged photographs of hawks killed by hunters and spread out across the ground. There is a similarly large photo of Rosalie Edge, the woman who saved the hawks and started the Hawk Mountain Sanctuary in 1935. Edge was a former socialite, who continued to dress like one, while becoming the most ardent bird conservationist of the New Deal era. She holds a hawk, symbolizing perhaps her own fierce commitment to the cause. Undeterred by rank or standing, Edge went to the swearing-in party of FDR’s confidante and new Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, and, without introduction, confronted him with the need to take strong and effective conservationist measures. Despite this rather brash beginning, Ridge and Ickes became close. This rather unusual duo carried out an effective inside-outside Washington strategy in which Ridge stirred up the public for conservationist demands that she and Ickes had plotted and collaborated on.

So it was that the far gentler, but equally determined, Rachel Carson was able to make her way to the North Lookout in 1945 where she wrote field notes later published by her biographer, Linda Lear, in Lost Woods: The Discovered Writing of Rachel Carson. Carson is clearly moved by the hawks who first appear in the distance like leaves blown in the wind before they sweep into full view. But she also muses about the ecology and evolution of her vistas. She writes of the formation of the ancient Appalachian Mountains — now worn down over the eons — and how they were formed from an ancient sea. “Halfway up the steep path to the lookout is a cliff formed of sandstone; long ago it was laid down under shallow marine waters where strange and unfamiliar fishes swam; then the seas receded, the mountains were uplifted, and now the wind and rain are crumbling the cliff away to the sandy particles that first composed it. And these whitened limestone rocks on which I am sitting — these, too, were formed under that Paleozoic ocean, of the myriad tiny skeletons of creatures that drifted in its water.”

Imagining evolution and its awesome and almost unfathomable mysteries is a frequent theme in Carson’s later, published works. Her great trilogy of ocean books that established her fame, appeal, and credibility as a writer allows readers to feel the majesty and the preciousness of modern creatures that have taken eons to achieve their current form and beauty. It is why Carson reluctantly, but ultimately, concluded that our species — with its atomic bombs, chemicals, and heedless efforts to control nature itself — was becoming dangerous.

But Rachel Carson also believed that teaching children a “sense of wonder” for all of creation could temper our impulse to control and to destroy. She would have welcomed the middle school students I saw clambering easily over the rocks, squealing with delight as even a lowly Turkey Vulture glides by on the wind. They marvel at Monarch butterflies that migrate here as well, at the incredible insect that actually is a walking stick, and at the spectacle of Sharp-Shinned hawks diving toward the stuffed owl mounted on a pole that the sanctuary staff has erected to lure the sharpies closer.

The staff research biologist, David Barber, armed with binoculars, a spotting scope, and a score sheet, introduces these kids to the lure and the lore of Hawk Mountain. The ridge that Rachel watched is still here, its distant bumps and slopes numbered one through five. Barber and expert birders near him call out distant sightings of hawks, bald eagles, a peregrine falcon — those tiny, floating leaves that Rachel saw. “Sharpie and a Cooper’s between two and one – moving right toward the Donat…” A pair of black vultures sail at us and land on a gnarled stump at the front edge of our rocks to the delight of our seventh graders. It is a female who feeds her croaking, full-grown child. Once entranced like this, both Rachel Carson and today’s teachers — who have brought these modern children to these ancient rocks — believe that the young will learn to care for all life forms and the earth around them.

Will such love and learning come soon enough? Barber and I talk about how there were no black vultures here at Hawk Mountain when Carson first came in 1945 or in 1972 when I first navigated the rivers of rocks that lead up this mountain. Black vultures did not arrive to be counted at the North Lookout until the 1990s – some twenty years ago. Now dozens of them nest nearby. It is the gradual warming of our climate by burning fossil fuels that has steadily moved these once southern birds to Pennsylvania. In the  nature center, as I leave for Washington in the afternoon, a staff member tells a small group seated beneath hanging models of hawks and eagles that Cooper’s Hawks, which formerly only migrated over Hawk Mountain, now winter here because of the milder temperatures. And when they do, they feed on smaller resident hawks like kestrels. The number of kestrels, as a result, is now noticeably reduced.

nature center, as I leave for Washington in the afternoon, a staff member tells a small group seated beneath hanging models of hawks and eagles that Cooper’s Hawks, which formerly only migrated over Hawk Mountain, now winter here because of the milder temperatures. And when they do, they feed on smaller resident hawks like kestrels. The number of kestrels, as a result, is now noticeably reduced.

When Rachel Carson leaned against the rocks of Hawk Mountain in 1945, October was gray, windy, frigid. “The cold is bitter,” she wrote, “…the cold seeps through to the very marrow of my bones.” Later, Carson learned about the earliest warnings of global climate change from Roger Revelle and others during the Kennedy Administration. Today, she would have ample confirmation of those fears. Hawk Mountain still offers wisdom for those who sit upon its rocks and watch the horizon for what may come. Rosalie Edge saw the slaughter of hawks in the thirties and rose up to stop it. In 1962, Rachel Carson wrote about Hawk Mountain in Silent Spring; how fewer and fewer juvenile eagles were being counted at the North Lookout because of DDT. Today at Hawk Mountain, where birders and biologists have kept count for several generations, the species that are observed are slowly changing. They and we are threatened as if by men with rifles and shotguns. But it is hard to see the destruction unless you watch and wonder and count and care. In the distance, I hear the laughter, giggling, shouting of the final group of students who have come to this sanctuary with their teachers. I think of one of them near me avidly making field notes. I smile. Perhaps, like Rosalie Edge or Rachel Carson, she will make a difference in our future.

Written by Dr. Robert K. Musil, President, Rachel Carson Council